TIME SENSITIVE:

LOOPER LOOKS BACK AT THE FUTURE

|

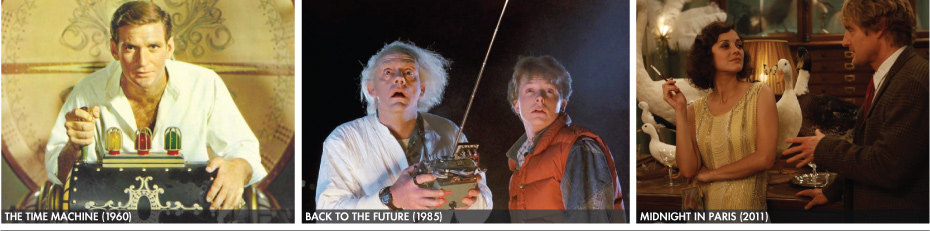

The allure of alternate futures, the power of potential predestination and the desire to rewrite history — time travel as a cinematic convention possesses a mystique that has long captured audience imagination. This month, writer/director Rian Johnson (BRICK, THE BROTHERS BLOOM) takes audiences back to the future and into that future’s past with LOOPER, a complex crime web spun from the threads of interwoven timelines. Re-teaming Johnson with BRICK star Joseph Gordon-Levitt (THE DARK KNIGHT RISES, INCEPTION), LOOPER is set in a dystopian near-future gangland ruled by a criminal organization even further along in the time stream. Gordon-Levitt plays Joseph Simmons, a “looper” — or assassin specializing in killing those condemned by future mob bosses and sent back in time. Things get complicated when Simmons recognizes his latest target as the future version of himself (played by Bruce Willis), igniting a deadly conflict between the present and future incarnations. It’s a narrative Rubik’s Cube, a temporal puzzle that offers wide-open storytelling opportunities alongside the high potential for plot-holes. Intrinsic to the notion of combining timelines is the problem of paradoxes, the inextricable relationship between past and present — and the effects they necessarily have on one another as both streams proceed toward their outcomes. “Time travel never makes sense,” Johnson told pop culture website COLLIDER.com. “What the best time travel movies do is deftly hide the fact that it doesn’t make sense… it’s almost like doing a magic trick. It’s figuring out which misdirection to do.” But that complexity is part of the appeal, and just one of the many bold creative traditions of the time travel trope — itself a versatile and quintessentially elastic construct allowing for infinite storytelling diversity in infinite combinations. “People just sort of accept the notion,” said Neil Canton, producer of the BACK TO THE FUTURE trilogy and Senior Filmmaker-in-Residence in Producing at the AFI Conservatory. “But it’s a device to help you tell your story. You can have someone warning you about the space-time continuum, and that’s fun. But it’s good storytelling when you’re rooting for the characters, when they’re good characters who work toward a good story.” A far more straightforward exemplar of the time travel pantheon is THE TIME MACHINE (1960), the science-fiction classic from genre luminary George Pal (DESTINATION MOON, THE WAR OF THE WORLDS), based on the peerless visionary work of legendary author H.G. Wells. Ripped from the pages of its speculative source material, Pal’s THE TIME MACHINE avoids paradoxes and narrative snags by keeping its focus on the distant future of the human race. By moving so far forward, the film establishes a unique perspective without concern for loopholes in the chronological thread.

“I love THE TIME MACHINE; it was my first exposure to a time travel story as a kid and it had a tremendous influence,” said Bob Gale, writer of the BACK TO THE FUTURE trilogy. “But what the work is, it’s just speculation. It’s allegory and supposition. It goes so far into the future that you’re not going to confuse it with anything; you may as well be on another planet. It’s not even a time travel movie so much as a science-fiction premise.” THE TIME MACHINE — iconic though it may be — is almost an exception to the time travel rule, an uncomplicated science-fiction anomaly in a “genre” that often defies such classification. Look no further than recent entries in the category to see the depth and breadth of the convention’s possibilities. While MEN IN BLACK 3 (2012) may also have reinforced the science-fiction underpinnings of time travel, recent releases such as SAFETY NOT GUARANTEED (2012), MIDNIGHT IN PARIS (2011), HOT TUB TIME MACHINE (2010) and THE TIME TRAVELER’S WIFE (2009) prove that the device can be used to excellent effect across wildly disparate genres — even without built-in timeline confusion. “Time travel itself is not a genre,” said Canton. “It’s more universal than that. Who wouldn’t want to go back in time? That’s what’s great about time travel; everyone wishes they could go back. Personally, I do. I just think the whole notion is so cool. Even though it’s unknown, it’s still known. Science-fiction feels like there should be spaceships out exploring the galaxy, and this lets you do something different.” And therein lies the inherent — and often overlooked — power of time travel as a narrative device. As effective as it is in complementing and enhancing science-fiction scenarios and stories, it can be so much more malleable — providing different genres with high-concept conventions that might otherwise seem to contradict them. “One of the interesting things about time travel is that it can cross genres,” said Gale. “I remember [Robert] Zemeckis saying that the first story we should recognize as time travel is "A Christmas Carol." What that shows you is that the device isn’t important. What’s important is how you can get the audience to suspend disbelief.” |

SAFETY NOT GUARANTEED is a quirky character study, using its time travel conceit to elevate a story of misfits on the fringe; whether or not the technology even works lends color to the narrative, but the focus is on its offbeat protagonists and their fractured relationships. Equally unconventional is MIDNIGHT IN PARIS, Woody Allen’s Oscar-nominated ode to the Jazz Age and La Belle Époque. Trading science-fiction for fantasy, the film celebrates the nostalgia of bygone days, transporting its protagonist by magical means to the Paris of the past. HOT TUB TIME MACHINE is a raucous, rowdy excuse to turn back the clock in order to keep the party going for an extra decade or so. They’re all different perspectives on common genres, affording filmmakers the opportunity to twist expectations and shape familiar formats into altogether new stories.

Easily one of the most prominent and popular examples of the formula, BACK TO THE FUTURE employs science-fiction conventions as a vehicle to invert them. Placing contemporary protagonist/teenager Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox) into the most conventional of unconventional settings — the squeaky clean streets of 1950s suburbia — it’s a far cry from flying cars and dystopian futures (both of which would later be immortalized in the sequel). Eschewing Einstein’s theory that surpassing the speed of light is essential to breaking the time barrier, BACK TO THE FUTURE achieves its period objectives favoring style over scientific substance, and at a far more filmable velocity — 88 mph in a souped-up, tricked-out DeLorean. “Eighty-eight is just kinda cool,” said Canton. “And you can get your own car up to 88, so it feels like something that anyone can do. Again, it’s universal. All you really need is a DeLorean.” The result, of course, is iconic and electric (1.21 gigawatts of electricity, to be precise) — not entirely due to of the predictive powers of the filmmakers, but because of the perspective that their narrative construct provided. It’s an opportunity to twist the vantage, to look at the periods — the present as well as the halcyon past — with outsiders’ eyes, and thereby find the humor inherent in both. It leads to some of the film’s best moments, but BACK TO THE FUTURE makes so much more of its premise than merely intertwining timelines. A big part of the fun is the juxtaposition of past and present sensibilities, of nostalgia and contemporary humor — neither of which plays to a particularly high concept, but neither of which would have been possible without time travel as a narrative device. ”The interesting part, for me, was always in the past, and the third film goes even deeper. Of course, you need time travel to get there. It works because you want Marty to follow Doc, because you’re invested in the story,” said Canton. “But it’s pretty low-tech. Just look at what Doc’s got to do to get an ice cube.” BACK TO THE FUTURE’s second sequel takes the device all the way back to the Old West — even further afield from hard sci-fi. It’s a wry commentary on time travel as a genre, and an indicator that it can sometimes be most effective when distanced from immersive futurism. This is a cinematic truth borne out by James Cameron’s high concept, low budget classic, THE TERMINATOR (1984), and even the fourth installment in the theatrical STAR TREK franchise (STAR TREK IV: THE VOYAGE HOME — 1986), which traded the final frontier for the streets of 1980s (then present day) San Francisco. These genre touchstones did more with less, developing their complex respective mythologies around ideas rather than relying on the far-flung production values typically associated with the genre. “Audiences want a good story. They want characters they can go along with,” said Gale. “The point is to have fun, to poke fun and to look at how things can change. There’s always the history conundrum and it can make zero sense, but that doesn’t matter when the misdirection’s well done. You’re not worried about that, because you want to go along for the ride. If you can travel through time, you can change things. And if you can change things, the future becomes a possible future and not the future.” A worthy entry into the pantheon of time travel movies, LOOPER looks to balance these various juxtapositions and contradictions, using its format to explore notions of fate and free will, destiny and identity. A creative realization of the classic approaches to time that have long characterized the genre, LOOPER builds a mythology of ideas with a striking future-noir production design adding depth to its dystopian visual worlds. Featuring high concepts and high-octane action, LOOPER lands in theaters on September 28 — not a moment too soon for time travel fans. |

|

|