You’re known for scoring stories of superheroes in major studio films. What other types of stories would you like to work on?

You’re known for scoring stories of superheroes in major studio films. What other types of stories would you like to work on?

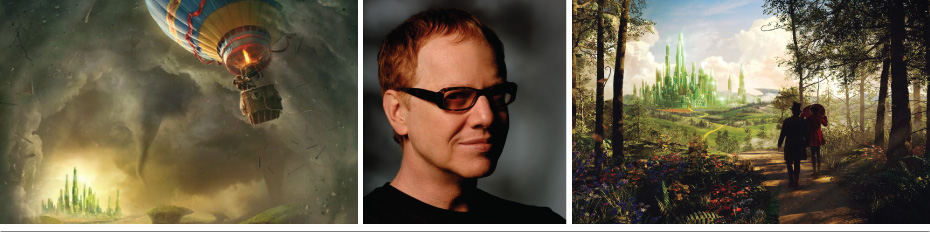

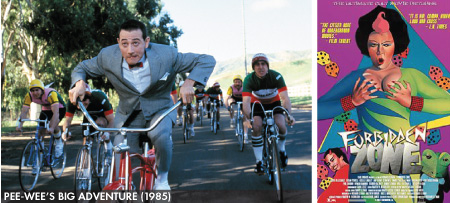

I like working on all kinds of stories. This year has been an exceptionally interesting and versatile one. Going from FRANKENWEENIE and DARK SHADOWS to HITCHCOCK, SILVER LININGS PLAYBOOK and PROMISED LAND to OZ THE GREAT AND POWERFUL and EPIC. I had the great fortune this year of really bouncing to extremes, and that is what I love most.

I like working on all kinds of stories. This year has been an exceptionally interesting and versatile one. Going from FRANKENWEENIE and DARK SHADOWS to HITCHCOCK, SILVER LININGS PLAYBOOK and PROMISED LAND to OZ THE GREAT AND POWERFUL and EPIC. I had the great fortune this year of really bouncing to extremes, and that is what I love most.

Do you work well under deadline pressure?

Do you work well under deadline pressure?

That’s the only way I work. Very often when I’m doing press stuff, they’ll be asking me, "What is your motivation when you sit down to write? What is your inspiration?" You never say the truth...

That’s the only way I work. Very often when I’m doing press stuff, they’ll be asking me, "What is your motivation when you sit down to write? What is your inspiration?" You never say the truth...

Which is...?

Which is...?

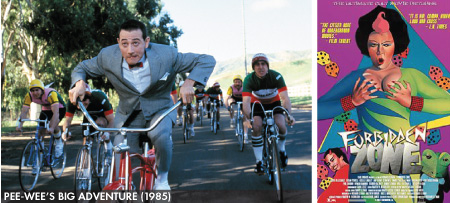

Deadlines! My inspiration is the deadline. If I didn’t have the deadline, I’d still be working on PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE. So my inspiration is motivated by the fact that "holy crap, my time is gone! I’ve got to get notes on the paper. I’ve got to get it down now!" Any film composer who’s successful and works well ultimately is motivated by pressure. I don’t consider myself a naturally disciplined person.

Deadlines! My inspiration is the deadline. If I didn’t have the deadline, I’d still be working on PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE. So my inspiration is motivated by the fact that "holy crap, my time is gone! I’ve got to get notes on the paper. I’ve got to get it down now!" Any film composer who’s successful and works well ultimately is motivated by pressure. I don’t consider myself a naturally disciplined person.

Do you spend a lot of time listening to new samples and trying to keep up with those synthetic sounds?

Do you spend a lot of time listening to new samples and trying to keep up with those synthetic sounds?

Well, I do as best I can, but in the end I hate everything. I work with what I work with. There are certain kinds of sounds that samples do better than others. If you’re doing a big action piece, a big aggressive piece, you can actually get the piece to sound really pretty good, but if you’re doing a very quiet or evocative piece, you know the soft playing of strings, the lack of vibrato in the samples – you know, it is what it is. It just gets you through the moment, but no one would ever mistake it for real strings.

Well, I do as best I can, but in the end I hate everything. I work with what I work with. There are certain kinds of sounds that samples do better than others. If you’re doing a big action piece, a big aggressive piece, you can actually get the piece to sound really pretty good, but if you’re doing a very quiet or evocative piece, you know the soft playing of strings, the lack of vibrato in the samples – you know, it is what it is. It just gets you through the moment, but no one would ever mistake it for real strings.

Was Bernard Herrmann an influence on your score for HITCHCOCK?

Was Bernard Herrmann an influence on your score for HITCHCOCK?

Well, Herrmann was probably a bigger influence on OZ than HITCHCOCK.

Well, Herrmann was probably a bigger influence on OZ than HITCHCOCK.

How so?

How so?

With HITCHCOCK, we made a conscious decision not to make it Herrmannesque. There were a few moments, of course, where I’m sure it did, almost unconsciously, because it’s so much a part of my own musical DNA. I’ll get Herrmannesque even when I’m not trying to get Herrmannesque. But because of the fantasy nature of OZ there were actually probably more moments where I was allowing myself to be Herrmannesque with my use of brass and woodwinds than in HITCHCOCK, where I was trying not to.

With HITCHCOCK, we made a conscious decision not to make it Herrmannesque. There were a few moments, of course, where I’m sure it did, almost unconsciously, because it’s so much a part of my own musical DNA. I’ll get Herrmannesque even when I’m not trying to get Herrmannesque. But because of the fantasy nature of OZ there were actually probably more moments where I was allowing myself to be Herrmannesque with my use of brass and woodwinds than in HITCHCOCK, where I was trying not to.

Did you have a mentor when you started out in this field?

Did you have a mentor when you started out in this field?

No, not at all. I got into film totally backwards. I had no mentor. I had no lessons. I was in a musical theatrical street troupe for seven years and it’s there I taught myself to write. Then, as you know, I was in a rock band for a number of years. But really, it was this bizarre combination of two things that catapulted me into film – both random. Tim Burton used to come and see Oingo Boingo, my band, and he seemed to think that I could do more with myself than I had shown; and Paul Reubens was a fan of this little cult film called FORBIDDEN ZONE that my brother [Richard Elfman] had done. I scored the movie with the Mystic Knights – not scored in the traditional sense, but, you know, I wrote tunes and did a little score. I never expected it to lead to other stuff. I did those and I went back to the band and it was all history until PEE-WEE popped up. And they were going through names and my name popped up. And Tim knew me through the rock band and Paul knew me through FORBIDDEN ZONE. So I got called in for an interview, and if anything I tried to say, "Why me?" I didn’t really get it.

No, not at all. I got into film totally backwards. I had no mentor. I had no lessons. I was in a musical theatrical street troupe for seven years and it’s there I taught myself to write. Then, as you know, I was in a rock band for a number of years. But really, it was this bizarre combination of two things that catapulted me into film – both random. Tim Burton used to come and see Oingo Boingo, my band, and he seemed to think that I could do more with myself than I had shown; and Paul Reubens was a fan of this little cult film called FORBIDDEN ZONE that my brother [Richard Elfman] had done. I scored the movie with the Mystic Knights – not scored in the traditional sense, but, you know, I wrote tunes and did a little score. I never expected it to lead to other stuff. I did those and I went back to the band and it was all history until PEE-WEE popped up. And they were going through names and my name popped up. And Tim knew me through the rock band and Paul knew me through FORBIDDEN ZONE. So I got called in for an interview, and if anything I tried to say, "Why me?" I didn’t really get it.

So when did you get it?

So when did you get it?

Right there on PEE-WEE, the first cue that I heard played back. I was hooked. But even when I wrote the score for PEE-WEE I expected it to be thrown out.

Right there on PEE-WEE, the first cue that I heard played back. I was hooked. But even when I wrote the score for PEE-WEE I expected it to be thrown out.

So this is something you’ve learned by doing. Do you mentor young composers now? Do you have a staff at your studio?

So this is something you’ve learned by doing. Do you mentor young composers now? Do you have a staff at your studio?

It’s a pretty lonely endeavor. I keep a very small crew. Of course, I have a staff, but I always prided myself in having one of the smallest crews in my profession. I have two people who work here at my studio every day. And I’ve had the same orchestrator since PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE – Steve Bartek, who was my guitarist in Oingo Boingo, who literally got the job by just going: "Hey, Steve, believe it or not, I’m getting hired to do a film score. I need an orchestrator. Have you ever done any?" And he said, "I took a class." And I said, "That’s good enough." But I never really mentored anyone, so to speak, because I don’t think I know how.

It’s a pretty lonely endeavor. I keep a very small crew. Of course, I have a staff, but I always prided myself in having one of the smallest crews in my profession. I have two people who work here at my studio every day. And I’ve had the same orchestrator since PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE – Steve Bartek, who was my guitarist in Oingo Boingo, who literally got the job by just going: "Hey, Steve, believe it or not, I’m getting hired to do a film score. I need an orchestrator. Have you ever done any?" And he said, "I took a class." And I said, "That’s good enough." But I never really mentored anyone, so to speak, because I don’t think I know how.

Your work for Tim Burton is now available in a box CD set. Have you listened to it straight through, and how did that affect you?

Your work for Tim Burton is now available in a box CD set. Have you listened to it straight through, and how did that affect you?

Well, yeah, I had to put that together. That was like three months of intensive work. And it’s the first time I ever listened to my past work. It was very weird because I really obsessively do not listen to anything I’ve ever done. Ever. Once I’ve made the soundtrack and the soundtrack is done, I never listen to it again unless I have to. To suddenly have to sift through 25 years of work was really interesting. It was really very strange. It was like, "Oh my God, did I write that? Oh my God, that was so primitive." Then at the end, I was like, "Well, that was primitive, but maybe I need to kind of learn something from that, too." It was really interesting. It was shocking. The funkiness of some of the recordings was also shocking.

Well, yeah, I had to put that together. That was like three months of intensive work. And it’s the first time I ever listened to my past work. It was very weird because I really obsessively do not listen to anything I’ve ever done. Ever. Once I’ve made the soundtrack and the soundtrack is done, I never listen to it again unless I have to. To suddenly have to sift through 25 years of work was really interesting. It was really very strange. It was like, "Oh my God, did I write that? Oh my God, that was so primitive." Then at the end, I was like, "Well, that was primitive, but maybe I need to kind of learn something from that, too." It was really interesting. It was shocking. The funkiness of some of the recordings was also shocking.

If you don’t ordinarily listen to Elfman, what or whom do you listen to?

If you don’t ordinarily listen to Elfman, what or whom do you listen to?

Well, I tend to listen to stuff only when I’m driving and only before I go to sleep because I’m writing all the time. So because I’m writing I never really get to listen to stuff, but when I’m driving I primarily listen to hip-hop. And when I’m at home I listen to – it’s pretty eclectic – I mean..."Armful of Parts," Radiohead, some Erik Satie, Shostakovich...I try to listen to things that are calming. It’s really about trying to get the tunes out of my head so I can go to sleep. It’s pretty practical. I will, if I’m not careful, continue writing in my sleep.

Well, I tend to listen to stuff only when I’m driving and only before I go to sleep because I’m writing all the time. So because I’m writing I never really get to listen to stuff, but when I’m driving I primarily listen to hip-hop. And when I’m at home I listen to – it’s pretty eclectic – I mean..."Armful of Parts," Radiohead, some Erik Satie, Shostakovich...I try to listen to things that are calming. It’s really about trying to get the tunes out of my head so I can go to sleep. It’s pretty practical. I will, if I’m not careful, continue writing in my sleep.

So you go from the snowy screen to the dark screen?

So you go from the snowy screen to the dark screen?

The snowy screen is just when I’m watching the screen for the first time. That’s where I’m blank. After that I’ve got to get incredibly focused. So there’s nothing snowy there. It’s like skipping from picture to picture to picture as I’m trying to hone in on what it is that’s necessary for each moment. What happens is that, in that process of working 12-hour days, sometimes it’s hard to let it go. I know it’s not a unique problem for me because, talking with other composers, I think it’s kind of a classic dilemma. You’re working and you’ve got these themes going, you’re working such long hours and you find yourself kind of looping music, and that’s kind of deadly. It leads to waking up feeling un-rested, but nothing accomplished by this so-called work you’re doing in your dream. I mean I’ve actually had extended dreams where I say in the dream "This is ridiculous, I’m dreaming!" And some technicians come out and go, "No, no, no... you’re hooked up to a hard-drive, everything you’re working on is getting saved." "Really?" "Absolutely." "This is fool-proof?" "In fact, there’s a redundant backup system, even if it crashes, everything’s being saved." So I continue writing, I continue working. And of course, I wake up, and it’s like "Nooooooo...!"

The snowy screen is just when I’m watching the screen for the first time. That’s where I’m blank. After that I’ve got to get incredibly focused. So there’s nothing snowy there. It’s like skipping from picture to picture to picture as I’m trying to hone in on what it is that’s necessary for each moment. What happens is that, in that process of working 12-hour days, sometimes it’s hard to let it go. I know it’s not a unique problem for me because, talking with other composers, I think it’s kind of a classic dilemma. You’re working and you’ve got these themes going, you’re working such long hours and you find yourself kind of looping music, and that’s kind of deadly. It leads to waking up feeling un-rested, but nothing accomplished by this so-called work you’re doing in your dream. I mean I’ve actually had extended dreams where I say in the dream "This is ridiculous, I’m dreaming!" And some technicians come out and go, "No, no, no... you’re hooked up to a hard-drive, everything you’re working on is getting saved." "Really?" "Absolutely." "This is fool-proof?" "In fact, there’s a redundant backup system, even if it crashes, everything’s being saved." So I continue writing, I continue working. And of course, I wake up, and it’s like "Nooooooo...!"