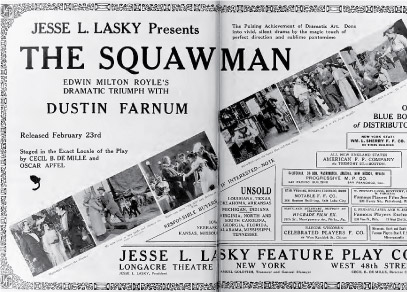

This month marks the centennial of the very first feature-length motion picture made in Hollywood: THE SQUAW MAN, directed by Oscar C. Apfel and Cecil B. DeMille from the play and novel by Edwin Milton Royle and produced by the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company. Film historian Robert S. Birchard, Editor of AFI's Catalog of Feature Films, granted us permission to reprint the following edited excerpt from his book, "Cecil B. DeMille's Hollywood," published by the University Press of Kentucky, which tells the somewhat harrowing story of this movie milestone in the making. We thank Mr. Birchard for sharing this account, which arrived too late to be included in the pages of the print version of American Film™, but seems right at home here.

WHY NOT THE MOVIES?

In the fall of 1913, Cecil B. DeMille faced a bleak future. He was 32 years old with a wife and daughter to support, and only a mountain of debt to show for his years in the theater. DeMille's wife, actress Constance Adams, showed great patience. His creditors, on the other hand, were becoming aggressively insistent that Mr. DeMille meet his outstanding obligations.

In the fall of 1913, Cecil B. DeMille faced a bleak future. He was 32 years old with a wife and daughter to support, and only a mountain of debt to show for his years in the theater. DeMille's wife, actress Constance Adams, showed great patience. His creditors, on the other hand, were becoming aggressively insistent that Mr. DeMille meet his outstanding obligations.

The possibility for even modest success in the theater was rapidly disappearing in 1913, and the reason was the movies. In the early 1900s, when Cecil DeMille first set foot on stage, there were well over 300 theatrical touring companies. By 1912, there were 200, and the number continued to decline. In New York City the devastation was even worse. Where once 40 theaters flourished with popular melodrama, only one still catered to that market in 1912.

The Broadway theater was alive and well, and vaudeville was in its heyday; but the audience for the "ten, twent', thirt"' shows had switched their allegiance to the "theater of science" where silent shadows danced on a silver screen. The most elaborate stage setting for a theatrical war horse like "The Squaw Man" could not compete with the genuine cactus and sagebrush seen in the one and two-reel oaters cranked by the likes of Broncho Billy Anderson in Niles, California; Romaine Fielding in Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado; or Thomas Ince in the Pacific Palisades near Los Angeles.

For a man of the theater it was easy to dismiss the movies as simplistic, childish, lacking in real dramatic values – but, principles aside, motion pictures had become the entertainment of choice for the largest segment of the audience.

At least one man believed in Cecil B. DeMille's talents, and that was producer Jesse L. Lasky. Along the way, Lasky and DeMille collaborated on several one-act operettas for the vaudeville stage, and the association led to a lasting friendship. But the royalties DeMille earned from his vaudeville playlets were not enough to live on, and even though he had an "unquestioned success" producing "The Reckless Age" on his own in the spring of 1913, by the fall Cecil was looking for a way out of his financial woes.

Jesse Lasky's brother-in-law was a glove salesman named Sam Goldfish. Sam was fascinated by the movies, and this fascination led him to study the picture business. He even mounted a one-man campaign to persuade Lasky to get into film production, but the vaudeville producer would have none of it. "When Sam kept urging me to start a picture company," Lasky wrote, "I told him hotly that I would have nothing to do with a business that chased people out of theatres..."

Over lunch one afternoon, DeMille confided to Lasky that he wanted an adventure. Perhaps he would check out the revolution raging in Mexico and write about his experiences. If DeMille was serious, and Jesse Lasky certainly thought he was, this sudden desire to become a foreign correspondent demonstrated just how desperately DeMille saw his situation.

Lasky made a sudden decision. If his friend wanted adventure, why not the movies? DeMille was excited. Goldfish was thrilled. And even though Lasky had grave doubts about the enterprise, the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company was formed with Lasky as president, Goldfish as general manager, DeMille as director general, and attorney Arthur Friend as secretary.

PREPARATIONS AND CASTING

PREPARATIONS AND CASTING

"The Squaw Man" seemed a natural for the new company's first production. It was a well-known play; author Edwin Milton Royle was willing to sell the motion picture rights at an affordable price; and being a Western, most of the action could be staged outdoors – eliminating the necessity for costly lighting equipment.

In preparation for making THE SQUAW MAN, Cecil B. DeMille spent a day at the Edison studio in the Bronx, observing how pictures were made. Despite (or perhaps because of) DeMille's day of training, it was felt that a production of the scope of THE SQUAW MAN required a director with more film experience. Oscar C. Apfel was selected to direct the production under DeMille's supervision. A veteran of the stage, Apfel made films for Edison, Reliance and Pathé before signing with Lasky. Along with Apfel came cinematographer Alfred Gandolfi, a fellow alumnus from Pathé who started his career at the Cines and Itala studios in his native Italy. Gandolfi claimed to have invented the lens shade and to be the first to shoot double-exposures in motion pictures. He later asserted that he was the first cameraman to use a foreground reflector in California.

Matinee idol Dustin Farnum was chosen to play the lead in the picture. A star of some standing in the theater, Farnum had appeared in "The Squaw Man" on stage (although William Faversham originated the role), but equally important, he had recently completed his first feature film role in SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE for the All-Star Feature Corporation.

The nature of Farnum's participation in the Lasky company's first production has long been a matter of dispute. DeMille claimed Farnum was offered a 25 per cent interest in the company in lieu of salary, but turned it down for a flat $250 a week. In Jesse Lasky's version Farnum agreed to the stock offer, but insisted on $5,000 in cash before leaving New York for the West.

In fact, Farnum's contract called for the actor to receive $250 a week for each week that he actually played before the camera, and "25 per cent of the net profits derived from the sale of the picture throughout the entire world." In later years Lasky and DeMille preferred to gloat over Farnum's lack of foresight in taking the stock, rather than admit that they had agreed to give away 25 per cent of the profits.

The selection of the leading lady for THE SQUAW MAN was a relatively simple matter. Winifred Kingston had been Dustin Farnum's co-star in SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, and more to the point, she was his leading lady off-screen as well. They later married.

Leaving Lasky and Goldfish in New York, DeMille and his small troupe set out for Flagstaff, Arizona, where they planned to shoot the picture. While on the train, he and Apfel set about adapting "The Squaw Man" into a suitable moving picture scenario. The rest of the cast and crew were to be picked up on location.

The mountain country around Flagstaff proved disappointing to the filmmakers. It did not suit the Wyoming locales specified in Royle's play, and even though many film companies had sent units to Arizona for winter filming, the location must have seemed incredibly remote. As DeMille remembered it: "When I got to Flagstaff there were high mountains, and I didn't want high mountains. I wanted plains with mountains in the distance... Dustin Farnum said to me, 'Well...I think we ought to go on to Los Angeles where the other picture companies are and have a look around.'"

The mountain country around Flagstaff proved disappointing to the filmmakers. It did not suit the Wyoming locales specified in Royle's play, and even though many film companies had sent units to Arizona for winter filming, the location must have seemed incredibly remote. As DeMille remembered it: "When I got to Flagstaff there were high mountains, and I didn't want high mountains. I wanted plains with mountains in the distance... Dustin Farnum said to me, 'Well...I think we ought to go on to Los Angeles where the other picture companies are and have a look around.'"

Arriving in the City of the Angels on December 20th, DeMille and company took up residence in the Alexandria Hotel. Today, despite a not-so-long-ago restoration, the Alexandria is a faded lady, but in 1913 it was the hotel of choice for travelers to L.A. Soon it also became the hub of motion picture deal-making, and the rug in the lobby was dubbed the "million dollar carpet" in honor of the many film deals that were consummated there.

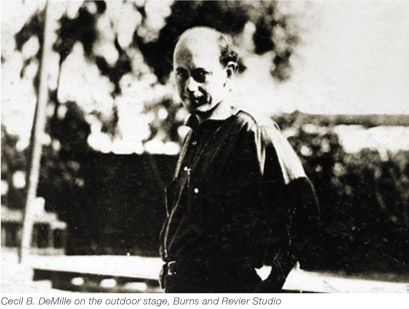

To round out the cast, the producers turned to the large pool of film and theatrical talent in Los Angeles. Dick Le Strange, who played Grouchy the ranch hand, was the first actor to be signed. A native of Germany, his stage career stretched back to 1900. DeMille's first choice for the role of Nat-U-Rich was Princess Mona Darkfeather. Darkfeather was billed as a full-blooded Seminole during her earliest days in pictures, but her real name was Josephine Workman, and by 1913, as the market for Indian-themed pictures began to wane, she claimed she was of Spanish descent and capable of playing a wide range of roles. Darkfeather and her husband, Frank Montgomery, were producing their own films independently for release through the Kalem Company, and she was not available to take the role in THE SQUAW MAN.

DeMille's second choice for the role of Nat-U-Rich was Red Wing. Born February 13, 1884, in Winnebago, Nebraska, Red Wing was a full-blooded Winnebago whose real name, phonetically at least, was Ah-Hoo-Sooch-Wing-Gah. She also used the Anglicized name of Lillian St. Cyr through much of her professional life.

Princess Red Wing started her picture career in the east with the Kalem Company as early as 1908 in a picture called THE WHITE SQUAW, but she first came to prominence with the Bison unit of the New York Motion Picture Company working with actor-director Charles K. French in THE COWBOY'S NARROW ESCAPE (released June, 1909). She spent a year with Bison and then went to work for the Western unit of Pathé Freres, where she again worked with Charles K. French and James Young Deer.

"I remember going to the Van Nuys Hotel to meet Mr. DeMille," Red Wing remembered in 1935. "He said I was too short. But just then Dustin Farnum, who played the lead, came in and looked at me and said, 'Don't go any farther; she'll do.' That's how I got the part."

Authenticity in Native American casting ended with Red Wing. Joseph Singleton, who played Tabywana, was Australian. He started his stage career Down Under and came to the States in 1894. After years in stock, his first film work was for Universal in 1912. He appeared in several features for Bosworth, Inc. before his assignment in THE SQUAW MAN.

SHOOTING BEGINS

SHOOTING BEGINS

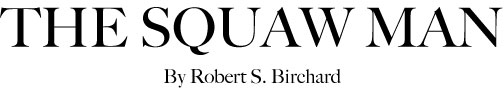

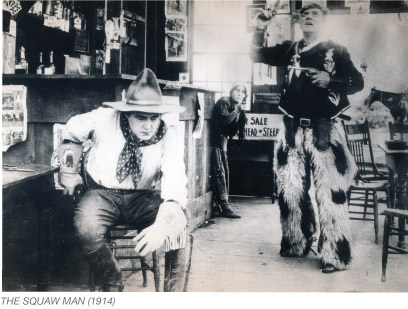

THE SQUAW MAN went before the camera on December 29, 1913, at the Burns & Revier studio. It is difficult to know just how much DeMille had to do with the direction of the picture. A photograph taken on the first day of shooting clearly shows Oscar Apfel directing, while DeMille stands with other members of the company off stage. Surviving prints give the credit "Produced by Oscar C. Apfel and Cecil B. DeMille" (the word "producer" meant director in 1914), but the main titles are from an early reissue, reflecting the graphic style of the Lasky films of the 1915-1916 period. It would be another four months before DeMille undertook direction of another picture on his own. However, if he was not actively involved in directing THE SQUAW MAN, he was certainly heavily involved in editing the picture.

The first scenes shot for THE SQUAW MAN were also the first scenes in the story – the dinner in the officers' barracks, the charity bazaar, and the theft of the funds by the Earl of Kerhill. With the exception of a few other interiors – a New York hotel room, a ship's stateroom, the Squaw Man's cabin, and Tabywana's teepee – the rest of the picture was shot on location.

Stories in the trade paper Moving Picture World told of the Lasky company's travels to Utah, Arizona, and Wyoming in search of authentic scenery, but DeMille and company never left southern California. Although the story opens in Britain, the scenes of the English Derby were bought from a stock footage service and inter-cut with scenes of Farnum, Kingston and Salisbury in a decidedly un-grand grandstand. Harbor scenes were shot in San Pedro, California, and the Western saloon set was built beside rail tracks in the vast desert that was the San Fernando Valley. The company did go as far afield as Keen Camp in Idyllwild and Hemet, California, to shoot footage of cattle on the open range and Mount Palomar for snow scenes. The English manor house was a mansion in the fashionable West Adams district of Los Angeles, and the exterior sets of the Squaw Man's cabin were built at the Universal ranch (now Forest Lawn Hollywood Hills). The imaginary stories of far-flung locations did help generate exhibitor interest, however, and Sam Goldfish took advantage of the publicity in selling the picture.

Principal photography took 18 days, and the production went smoothly enough on the set, but there were serious and potentially deadly problems off-stage. Aware that the nitrate film stock they were using was highly flammable, DeMille ordered two usable takes shot on every scene – one negative to be stored at the studio, the other at the Director General's rented home.

One night, DeMille went to the laboratory and found a length of the precious SQUAW MAN negative unspooled on the floor and irreparably damaged. Another evening, while riding home on horseback through the Cahuenga Pass, a bushwhacker took a shot at him. It was assumed that the incidents were perpetrated by goons hired by the Motion Picture Patents Company who sought to curtail independent production, though in interviews conducted for his own autobiography DeMille refused to blame the Patents Company and hinted that the acts might have been perpetrated by a lab technician he had fired. In any event, the culprits were never caught.

A NIGHTMARE SCREENING

A NIGHTMARE SCREENING

By the end of January 1914, THE SQUAW MAN was cut and titled. Jesse Lasky later claimed he came West for the first screening, and related that, "Everyone connected with the picture...was invited to the first showing in the barn. It was such a proud occasion that the men put on collars and coats and brought their wives. There were about fifty of us."

According to Lasky, he crossed his fingers as the operator began to crank the projector. The six reels of film represented an investment of $15,450.25 – his own money, and also the money of family and friends. THE SQUAW MAN had to be a success.

Then, as if in a nightmare, the picture jumped and staggered on the screen, stubbornly refusing to stay in frame. They checked the projector and found it to be in perfect working order. The problem was with the film itself, and it looked as if Lasky's motion picture career would be over before it had begun. Reluctantly, Lasky and DeMille wired Sam Goldfish to break the bad news. At least this is the story that both Lasky and DeMille related in their autobiographies. The truth, as far as it can be pieced together from copies of original telegrams between DeMille and Goldfish was considered much less of a disaster at the time than it seemed when filtered through 40-odd years of memory and retelling.

There was a problem with at least part of THE SQUAW MAN negative, which resulted from misperforated sprocket holes in the film stock. There were 65 perforations to the foot instead of the customary 64, and this caused the frame line to roll on screen when the picture was projected.

DeMille did not seem overly concerned about the problem, though he was certainly aware of it. He wired Sam Goldfish on January 24, 1914:

CAN'T ARRANGE PERFORATION UNLESS YOU CAN FORCE EASTMAN TO GIVE YOU POSITIVE [PRINT FILM] TO MATCH FIRST NEGATIVE. [OR] RUSH PERFORATING MACHINE...WITH FIFTY THOUSAND FEET UNPERFORATED POSITIVE...SQUAW MAN A GREAT PICTURE. CAN SEND FIRST PRINT FIVE DAYS AFTER RECEIVING PERFORATOR OR SIXTY-FIVE [PERFORATIONS TO THE FOOT] POSITIVE.

It is obvious from this telegram that DeMille believed that simply matching the number of sprocket hole perforations on the positive prints to the 65 perforation negative would solve the problem. This was incorrect, of course. The projector sprocket wheels would still turn at the rate of 64 to the foot, and the picture would still appear to roll. However, the problem was not considered a crisis.

Several days later he wired:

RAN "SQUAW MAN'' COMPLETE FOR FIRST TIME. ALL WHO SAW IT VERY ENTHUSIASTIC. FARNUM WILL DELIVER TO YOU SUNDAY NIGHT. PROPER CUTTING TAKES GREAT DEAL OF TIME. [THE PICTURE] RUNS JUST SIX THOUSAND FEET...YOU MAY BE SATISFIED YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE.

There is no evidence that Lasky was present at the Hollywood screening, nor is there any indication there was a problem with the film. The fact that Dustin Farnum would carry the print on his return to New York strongly suggests DeMille felt no apprehension about the picture.

In later years, while being interviewed by Art Arthur in preparation for writing his autobiography, DeMille stated: "I think [Jesse Lasky] recollected wrong. It did run off the screen here [in Hollywood], but not as badly as it did there [in New York]. I think probably because our operator or whoever was running the projection machine was alert to where it [the problem] came and was ready with the framing. You could frame it quite easily, you know. Then it would run alright for awhile, and then it would go off [frame] again."

There is no question, however, that when Sam Goldfish saw THE SQUAW MAN in New York the rolling image made the picture unmarketable. One simply couldn't rely on projectionists in hundreds of theaters to constantly ride herd on the framing lever through the film's 90-minute running time.

PROBLEM SOLVED

PROBLEM SOLVED

Faced with potential disaster, Goldfish decided on a desperate course of action. He arranged for DeMille to take THE SQUAW MAN to the Lubin Manufacturing Company in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, generally acknowledged to have the finest motion picture laboratory facilities in the United States.

As a member of the Patents Company, Lubin was theoretically unable to take work from independent producers. However, Sigmund Lubin, affectionately known as "Pop," was a bit of a rebel. In his earlier years in the business he had run afoul of Edison's patents himself and was forced to leave the country for a time to avoid the long arm of the Edison attorneys. Now he was in the "establishment" but not of it, and he agreed to help the novice filmmakers.

The Lubin laboratory glued a celluloid strip over the existing sprocket holes in the problem areas and reperforated the film. In extant prints of THE SQUAW MAN several scenes are splattered with white sprocket-hole-shaped "snowflakes." During re-perforation, bits of celluloid adhered to the negative and "printed through," causing them to show up on screen when the picture is projected.

In solving the problem, Lubin earned a contract for Lasky's release printing, and THE SQUAW MAN was finally screened for an invitational trade show audience at the Longacre Theater in New York on February 17, 1914.

As a movie, THE SQUAW MAN was more of a moving illustration than a work of real dramatic power. Somewhat cryptic in its presentation – especially in the early scenes which establish the motivation for Jim Wynnegate's self-exile to the American West – the film requires a certain familiarity with the source play and does not measure up to the best Biograph and Vitagraph shorts of the period. But 1913 audiences were acquainted with the play, which had toured the country in various forms since 1906, and were eager for longer narrative films with established stage stars.

With no national distribution network, the Lasky Feature Play Company sold THE SQUAW MAN on a state rights basis – territory by territory. Within two weeks of the February 17th trade screening, the Lasky Feature Play Company sold 31 of the 48 state territories. A week later, only Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska were up for grabs, and they soon fell into line.

A list of costs and grosses on all of his pictures prepared for Cecil DeMille in 1936 lists THE SQUAW MAN as having shown a net producer's profit of $244,700 – an extraordinary figure for 1914, and far in advance of anything his other pictures would do over the next several years. The figure is somewhat suspect, but there is no question that for Lasky, Goldfish and DeMille the picture was a spectacular success.

The triumph of THE SQUAW MAN was noted by W. W. Hodkinson, whose Progressive Motion Picture Company held the West Coast rights to the Lasky production. With exhibitors clamoring for feature pictures, Hodkinson dreamed of setting up a national distribution organization that could guarantee theater owners 52 feature pictures a year, much as the older established distributors were able to provide a full program of short films. Hodkinson joined forces with a number of regional distributors to form Paramount Pictures in May 1914 and contracted with Bosworth, Inc., Adolph Zukor's Famous Players Film Company, and the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company to produce pictures for the Paramount program.

Copyright © 2004 and 2014 by Robert S. Birchard