DRAWING CONCLUSIONS ABOUT BATMAN

|

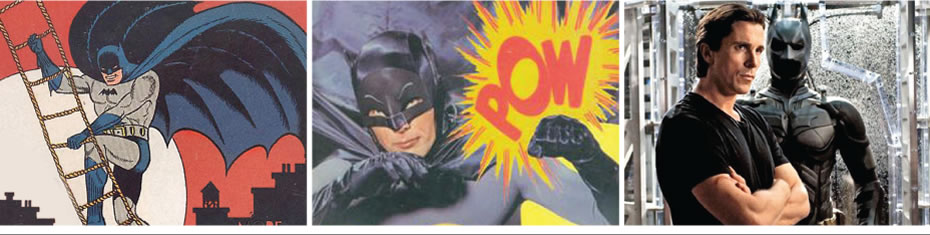

The end is near. Just listen to director Christopher Nolan: "We want to finish our story rather than infinitely blowing up the balloon and expanding the story," Nolan has said of THE DARK KNIGHT RISES, the third film in his Batman trilogy, which opens July 20. "Unlike the comics, these things don't go on forever in film. Viewing it as a an ending sets you very much on the right track about the appropriate conclusion." Have we arrived then at the conclusion of the Caped Crusader? Perhaps. Perhaps not. Let's go back to the beginning and see what led us to this bat-moment. It was May 1939 when artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger launched the character of "The Batman" in issue #37 of Detective Comics. America was looking for new heroes to step up to the plate and face Hitler and Mussolini. That month, baseball's "Iron horse," Lou Gehrig, had ended his consecutive game streak at 2,130, and Germany and Italy had signed the "Pact of Steel." By 1940, Batman had his own popular series for DC Comics as the superhero with no superpowers. The young Bruce Wayne had witnessed the murder of his parents and willed himself to master martial arts, using detective skills as well as his family fortune and connections to fight for justice as Batman. Like the "mild-mannered" Clark Kent who changed into Superman when needed, Wayne's playboy image belied his true nature, that when called upon he could do the world's dirty work as The Dark Knight. When America entered the Second World War, young men and boys saw themselves in Batman as they donned army uniforms and prepared for their own reckoning with evil. Of course, nobody needed to draft Batman to fight crime; he enlisted in that battle on his own. A generation later, with America again at war, this time in Southeast Asia, Batman swooped into television. Boom! Splat! Ka-pow! With its eye-popping graphics and catchy theme music by Neal Hefti, the 1966 series starring Adam West and Bruce Ward became enormously popular with baby boomers, but for entirely different reasons and with a different sensibility. "Because of the Vietnam War, we didn't take Batman seriously anymore," said James Hosney, AFI Distinguished Scholar-in-Residence, who has taught at the AFI Conservatory since 1980. "So the superhero became a camp figure. Even the first SUPERMAN (1978), the one directed by Richard Donner, bordered on camp, but not like that series. It was a send-up of the idea of the superhero. It became the superhero as seen through the veil of Andy Warhol, the whole idea of the pop sensibility. That was the only way to make a superhero palatable to the counter-culture." Hosney views Tim Burton's BATMAN (1989) and BATMAN RETURNS (1992) as "very controlled, but there's a comic tone with Tim Burton's black comic sense of humor." He found the third and fourth in that series, BATMAN FOREVER (1995) and BATMAN AND ROBIN (1997) directed by Joel Schumacher, consistent with Burton's approach. One aspect of the earlier Batman and Superman films that Nolan retained was the casting of major stars in secondary roles. In addition to Christian Bale in the role previously played by Michael Keaton, Val Kilmer and George Clooney, THE DARK KNIGHT RISES cast includes Michael Caine, Marion Cotillard, Morgan Freeman, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Tom Hardy, Anne Hathaway, Matthew Modine, Liam Neeson and Gary Oldman.

Christopher Nolan's "re-boot" began with BATMAN BEGINS (2005). "Nolan's Batman movies are so different from the first three," said Hosney. "When I saw THE DARK KNIGHT, I couldn't believe that this was a studio summer film," the scholar admitted. "I found it really disturbing and bordering on nihilism. It doesn't quite go there, but it is that border. And Heath Ledger's performance is so powerful that it unnerves you. If you compare that with Jack Nicholson's Joker, there's a chasm between the two. The whole tone of the film is dark." |

Cinematographer Wally Pfister, an AFI Conservatory alumnus from the class of 1989, has shot all of Nolan's films since MEMENTO (2000). "He came to AFI with THE DARK KNIGHT and told us that, once the studio gave the go ahead on the film, there was no interference whatsoever about 'this material's too dark' or 'where are you going with this?,'" Hosney recalled. As for the film's PG-13 rating, Hosney explained, "it isn't the psychological disturbance of the movie; it's that they never show blood spurt. People are killed and you have this darkness, but with no blood spurting, you don't get an R rating." Hosney believes the darkness of Nolan's Batman derives from the concept of vigilante justice. He cites three films released in December 1971: Stanley Kubrick's A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, DIRTY HARRY starring Clint Eastwood and Sam Peckinpah's STRAW DOGS as that year's trifecta of Christmas movies celebrating do-it-yourself crime fighting.

"DIRTY HARRY is an ennobling of vigilante justice," said Hosney. "I love the movie, but the idea is that the law is crazy because those who administer it will find a way to release a dangerous criminal, so the vigilante has to take the law into his own hands." Another film in this vein was DEATH WISH (1974), starring Charles Bronson as an architect turned one-man death squad following his wife's murder by street punks. Ten years later, life imitated art when Bernhard Goetz, the bespectacled "Subway Vigilante," shot four alleged muggers on the Number Two train in Manhattan with an unlicensed handgun. The first DIRTY HARRY film has an "incredible integrity" according to Hosney because, after Clint Eastwood's character takes the law into his own hands, he throws his badge in the water. "The last image – it's HIGH NOON (1952)," said Hosney. "He realizes he's stepped over a limit, and he's not part of this force because he's gone outside of it." Hosney pointed out that Christopher Nolan is known to be devoted to shooting on film, almost to the point of refusing to shoot with digital cameras. "He had that special screening in December for these high-powered people in Hollywood of eight minutes of THE DARK KNIGHT RISES to plead with them, to plead with the studios, to allow directors to have at least the choice of shooting in film. And it's not just film vs. digital media. When Wally Pfister screened THE DARK KNIGHT at AFI Conservatory, he told us that the action sequences were shot in IMAX. He said it really makes a difference. I went back and saw it when it was reissued and saw it again in IMAX. And it does make a difference! The detail you get on that, I've never seen before. And as I understand it, over an hour of the new film is shot on IMAX." To Hosney, Nolan's technically enhanced hyperrealism and the idea that a filmmaker shoots on film contain vestiges of the auteur theory of filmmaking. "This person seems determined to maintain his artistic integrity while working within a studio system," said Hosney. "I wonder: to what degree does he identify with Batman?" Hosney references Nolan's lNCEPTION (2010) as an indicator of his filmmaker integrity. "Can you think of another multi-million dollar studio film that has an ending that ambiguous, where you have no idea if you're in reality or this is one more version of reality?," he asks. The scholar admiringly compares that film to LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD (1961), an earlier classic film Nolan hadn't seen but which influenced him nonetheless. "I read an interview with Nolan that really impressed me," said Hosney, "where he said critics had criticized him for ripping off LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD – he had never seen it, so he watched it and then he said he realized 'that I was ripping off films that had ripped off LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD' – but for a contemporary director of a summer pop film to even deal with that kind of storytelling, where you're inter-cutting between at least three different narratives..." His voice trailed off, his eyebrows rose incredulously. Hosney's conclusion? He can't wait to see THE DARK KNIGHT RISES. |

|

|

According to the film's press book, THE DARK KNIGHT (2008) was the first major feature film production to have been "even partially shot" by IMAX cameras. The six IMAX sequences included a chase and the approximately six-minute-long opening scenes of an elaborate bank robbery. Shortly after the film's theatrical release, a full IMAX version was exhibited at specially equipped IMAX theatres. For more on Christopher Nolan’s THE DARK KNIGHT, visit the AFI Catalog of Feature Films. |