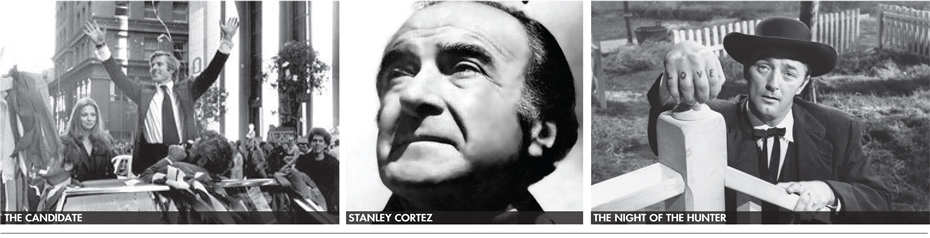

WHERE CINEMATOGRAPHER STANLEY CORTEZ FOUND INSPIRATION

|

Cinematographer Stanley Cortez (Orson Welles’ THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS, THE CANDIDATE) spoke at the AFI Conservatory on October 19, 1974. The Oscar®-nominated Cortez began his career as a portrait photographer, working with Pirie MacDonald and Edward Steichen. He decided to become a motion picture cameraman on a visit to the Paramount Studios on Long Island where D.W. Griffith was shooting SORROWS OF SATAN. (His brother, Ricardo, had a role in the film.) Cortez moved to Hollywood and worked his way up from assistant to camera operator – designing a camera movement in Busby Berkeley’s “Lullabye of Broadway” musical number – until becoming a cinematographer in 1937 with FOUR DAYS’ WONDER. He concluded his talk to the AFI Fellows with this piece of advice: “What am I talking about? Specifically, this: you walk out onto a soundstage. It’s black and the sequence calls for so-and-so and so-and-so. You might have a preconceived idea, but how do you actually start? For some people, perhaps, everything that they have experienced in their lives comes to a focal point, and from that point, ideas build upon ideas. I will always spend a great deal of time in museums, studying various paintings. I’ll study certain musical compositions because they give me something. I’ll go to New York and spend two days in the Metropolitan, or at the Louvre in Paris, or in Florence or Rome and God knows where else, because I’ll tell you, it all ties into being exposed to what’s happening in the world, so that we, as a creative group, can reflect, in terms of cinematic images, on what the hell this is all about. Let me give you the example of when I shot NIGHT OF THE HUNTER for Charles Laughton. We did many films together with him as an actor before he asked me to do HUNTER. We were shooting a particular sequence, and Laughton saw me doing a couple of things. ‘What in hell are you doing, Cortez?,’ he said. ‘None of your goddam business, Laughton,’ I said – in a very nice, lovable way, don’t get me wrong. The respect was there. But he insisted that I tell him what I was doing. ‘Charles, I’m thinking about a piece of music.’ And in his particular way, he said to me, ‘My God, Stan, how right you are. This sequence needs a waltz tempo.’ And so he immediately sent for the composer, Walter Schumann, so he could see what I was doing visually, so he could interpret it into a waltz tempo. |

Now, some of you may know the story behind Valse Triste by Sibelius, which fit perfectly with this whole sequence. The music is based upon a legend, and the legend has to do with New Year’s Eve in a cemetery. It’s one minute past midnight when these bones that have been buried come to life and do a dance in sheer mockery of life, which was precisely what Bob Mitchum was doing to Shelley Winters in the scene we were shooting. So what I’m trying to say to you is that people in the creative fields need stimuli. In my world, it’s music. Perhaps in yours it’s something else. So go into a museum, talk to a beggar on the street, go to the Sistine Chapel and see how the forced perspective was designed. Go anywhere, but look, see, hear, feel. Let me just finish by saying that I believe that with maturity as a creative artist comes simplicity. To become gimmicky with a camera, with a zoom lens – I don’t go for that sort of thing. The most difficult thing in the world is to be simple. And the enthusiasm must always be there, of course. Otherwise you’re dead.” |

|

|

A passage spoken by Orson Welles opens the Tarkington novel. Production credits are withheld until the end of the film when Welles's voice intones, "Ladies and gentlemen, THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS was based on Booth Tarkington's novel." An image of the novel then appears on the screen. As a movie camera flashes across the screen, Welles declares, "Stanley Cortez was the photographer." For more on THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS, visit the AFI Catalog of Feature Films |