TOUGH GUYS RAISE TOUGH QUESTIONS

|

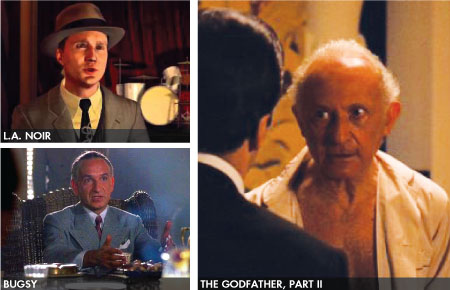

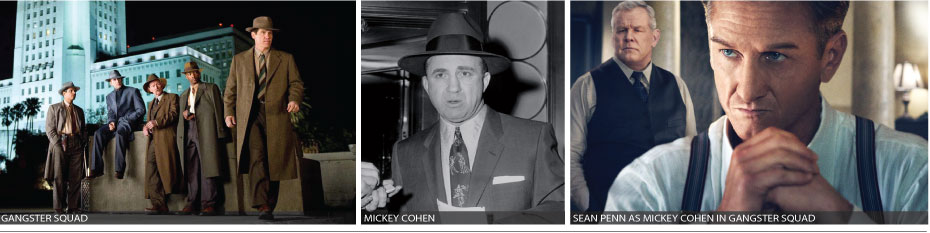

“Back east I was ‘a gengsteh,’ out here I’m God.” That’s Mickey Cohen in a moment of hubris from GANGSTER SQUAD. It will be up to a freshly minted squad of L.A. undercover cops (Josh Brolin and Ryan Gosling among them) to cut the crime boss down to size. Penn’s delivery speaks volumes. The pronounced and self-conscious Yiddish accent on the word gangster can be taken as an incredulous nod to his character’s humble origins, an honorific bestowed upon a fighter who has just moved up in weight class. There’s no trace of the sing-song inflection comparing “Back east,” on the one hand (as Tevye would say in FIDDLER ON THE ROOF), and “out here” on the other. No, Cohen is a movie tough guy, not a Broadway musical Jew. GANGSTER SQUAD is the latest in a string of Hollywood shoot ‘em ups to portray Cohen, a mobster who ran with Al Capone and Meyer Lansky. This Brooklyn-born son of an immigrant from Kiev, Ukraine, who fought his way out of the ghetto in fixed prizefights, has previously been played by Harvey Keitel in BUGSY (1991), Paul Guilfoyle in L.A. CONFIDENTIAL (1997) and Seth Gordon in THE OTHER SIDE (2004). On television, Harris Laskaway (SHAKEDOWN ON THE SUNSET STRIP), James Woods (FALLEN ANGELS) and Alan Woolf (THE RAT PACK) have all played Cohen. Cohen himself added to his notoriety on national television when Mike Wallace interviewed him in 1957. Today, there’s even a Mickey Cohen character in a video game, “L.A. Noir,” with Patrick Fischler doing the dishonorable honors. GANGSTER SQUAD offers Hollywood’s latest take on the image of the Jewish gangster in film, a rogue’s gallery that includes Arnold Rothstein (Michael Lerner in EIGHT MEN OUT), who fixed the 1919 World Series; Meyer Lansky (Sir Ben Kingsley in BUGSY), known as the “mob’s accountant”; and numerous fictitious kingpins and hit men, most notably Hyman Roth (Lee Strasberg in THE GODFATHER, PART II), Bo Weinberg (Bruce Willis in BILLY BATHGATE), The Rabbi (Kingsley again, in LUCKY NUMBER SLEVIN) and Peter Sarsgaard (David Goldman in the British import AN EDUCATION).

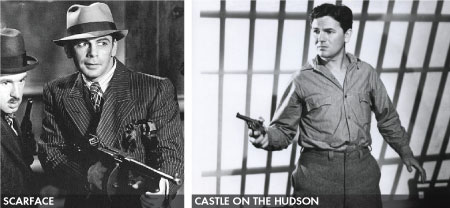

Judging from the title of the 30th Anniversary program of San Francisco’s 2010 Jewish Film Festival – “Tough Guys: Images of Jewish Gangsters in Film” – many in the Jewish community of today are willing to air what was once considered “dirty laundry” in the public square, yet the subject has a rich history, freighted with controversy. Historically, it has been a struggle for Jews, let alone Jewish gangsters, to be portrayed on a movie screen. “From its earliest days, Hollywood was ill at ease with its Jewish identity,” wrote James Greenberg in “The Jewish Problem” from the July/August 1988 issue of American Film™. “In many ways, it still is. The overt anti-Semitism of the old-line Bel Air nobility and Howard Hughes crowd may be gone. But it has been replaced, in some cases, by a corporate-style whitewashing of all ethnic traces.” Screenwriter Steve Shagan (SAVE THE TIGER) remarked in the same article that, “in the past, Hollywood’s own Jewishness precluded making films about Jews.” The subject of Jewish gangsters was swept under the rug by studio moguls from Eastern Europe anxious to avoid a shondeh (Yiddish, for disgrace) and eager to establish their wholesome, all-American credentials in order to gain acceptance – measured in weekly box office grosses – and assimilate. Interestingly, this prohibition did not preclude Jewish actors from playing Italian immigrants who rose from the neighboring slums via La Cosa Nostra. Edward G. Robinson (born Emanuel Goldenberg) triumphed as an Italian mobster named Rico in LITTLE CAESAR (1931) and thereafter a generation of standup impersonators adopted Robinson’s nasal, growling rant to a “crummy, flat-footed copper” as the definitive voice of the mob. Yiddish theater veteran Paul Muni (born Meshilem Meier Weisenfreund) made his mark as Al Capone in SCARFACE (1932). When SCARFACE was in its early stages of development by Howard Hawks, the Hays Office asked a psychologist, Dr. Carleton Simon, to advise the director. After reading a draft scenario in June 1931, Simon recommended that the character of "Epstein," apparently a defense attorney for the mobster in the original scenario, "should not be so pronouncedly Jewish...as it will react, at least racially, against the picture." |

Director Paul Sloane’s STRAIGHT IS THE WAY (1934) is an exception to the Jews-can-play-gangsters-as-long-as-they’re-Italian rule. The film, based on a Broadway play of 1927, stars Franchot Tone as Benny Horowitz, an ex-con trying to resist overtures from the mob. Its theme, a central one in Jewish literature, is the struggle to become a mensch, or ethical human being and, in the end, good triumphs over evil. It is noteworthy that Tone was of Irish, French and Basque ancestry. Casting a Jew in a Jewish role would have been pushing it in those days; and the one thing Jewish filmmakers of that generation did not want to seem was “pushy,” a common stereotype. John Garfield (born Jacob Julius Garfinkle) who specialized in playing sensitive tough guys, portrayed a mobster with the ethnically ambiguous name of Tommy Gordon in CASTLE ON THE HUDSON (1940), and critically, like Benny Horowitz, Gordon was trying to go straight.

After World War II, the Mickey Cohens of this world acquired a new significance. “In the post-Holocaust era, images of imposing Jewish men have had an obvious role in putting back together the pieces of a shattered identity,” observed Bay Area writer and teacher Joanna Steinhardt in “Zeek, A Jewish Journal of Thought and Culture.” “It’s become almost a given that stories and images of vengeful Jews compensate for the emasculated stereotypes of Ashkenazi Jewish men, the victim complex created by millennia of persecution and then genocide.” Steinhardt cites the proliferation of Jewish gangsters in post-war movies as proof that assimilated American Jews no longer feel paranoid, Woody Allen’s nebbishy (milquetoast) roles notwithstanding. “It seems that memories of our past as American gangsters is a way to remind ourselves that we weren’t always the comfortable, accepted, middle-class white people we are today.” In the 1960s and ‘70s, as middle class Jewish families continued moving to the suburbs, the Jewish gangsters on screen stayed rooted in the old neighborhood. The Brownsville section of Brooklyn, New York, was home to the so-called syndicate, aka “Murder, Inc.” Peter Falk made a name for himself playing Abe Reles (“What I want, I take!”) in MURDER, INC. (1960). Tony Curtis (born Bernard Schwartz) played Reles’ crime boss in the title role of LEPKE (1975), another look at the underbelly of Brownsville. Gangsters, according to Steinhardt, were “Jews without identity issues. They knew who they were…Jewish gangsters seem to blur the boundaries of whiteness and remind us that there was a time when all Jews were looked upon as alien, threatening and violent…encoded in the image of the Jewish gangster is a glimmer of authenticity. It’s as if, in this dark incarnation, we see the kernel of communal attachment that makes Jews Jews...Jewish gangsters remind us that we didn’t always have it so easy. We were once considered the dregs of American society and we had to struggle to make it. Once upon a time, before we were white.” To Abraham H. Foxman who, as National Director of the Anti-Defamation League, has long been the global media’s go-to spokesperson on matters concerning the public image of Jews, the portrayal of Jewish gangsters in films, while not beneficial to the Jewish community, is less a matter of anti-Semitism than insensitivity on the part of filmmakers for the sake of titillation and box office appeal. “Movie gangsters are made to seem more Jewish and unassimilated than they were; it’s an exaggeration that troubles me,” said Foxman. “As long as Jews continue to be on the top of the hit parade of stereotypes, the portrayal of Jewish gangsters gives ammunition to conspiracy theorists.” The Six Day War in 1967 elevated the Israeli soldier as an equally imposing cultural counterweight to the image of the Jewish gangster, which all but disappeared from screens until Strasberg’s memorable turn as Hyman Roth, the cunning, ruthless yet frail and folksy partner of Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) in THE GODFATHER, PART II (1974). Later, Robert De Niro, reversing the cross-ethnic career trajectory of Robinson and Muni, assayed the roles of David “Noodles” Aronson in ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA (1984) and Sam “Ace” Rothstein in CASINO (1995). Now GANGSTER SQUAD arrives at a time when a new wave of Jewish immigrants, including gangsters – this time from the former Soviet Union – makes headlines from Brighton Beach, Brooklyn to Beverly Hills. The film’s release follows years of Jewish-American ambivalence, reflected by the public debate between progressive Jewish intellectuals and mainstream organizations like the American Jewish Committee over the protracted Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Israeli Defense Forces are no longer as easily and universally exalted as the underdog heroes of the Six Day War. Those early moguls would doubtless find it hard to believe that, with such possible exceptions of Adam Sandler’s YOU DON’T MESS WITH THE ZOHAN (2008) and Steven Spielberg’s MUNICH (2005), the image of the Jewish man of action is back in the hands of mobsters – at least in GANGSTER SQUAD. |

|

|