When Seth MacFarlane’s Western comedy, A MILLION WAYS TO DIE IN THE WEST, moseys into theaters on May 30, moviegoers ought to feel right at home on the range and back in the blazing saddle again. No sooner had early Hollywood converted the pulp Western romance into celluloid than the wise guys rode in, poking fun at the “horse operas” and serial “oaters.” They sent up conventions of melodrama and the highfalutin Western themes of Cowboys vs. Indians, Man vs. Nature, Good vs. Evil, Godliness vs. Greed, and Justice for All. Stick ‘em up violence became the stuff of punch lines when audience familiarity with its conventions made the Western ripe for spoofing and satire.

When Seth MacFarlane’s Western comedy, A MILLION WAYS TO DIE IN THE WEST, moseys into theaters on May 30, moviegoers ought to feel right at home on the range and back in the blazing saddle again. No sooner had early Hollywood converted the pulp Western romance into celluloid than the wise guys rode in, poking fun at the “horse operas” and serial “oaters.” They sent up conventions of melodrama and the highfalutin Western themes of Cowboys vs. Indians, Man vs. Nature, Good vs. Evil, Godliness vs. Greed, and Justice for All. Stick ‘em up violence became the stuff of punch lines when audience familiarity with its conventions made the Western ripe for spoofing and satire.

It didn’t take long. Just three years after Cecil B. DeMille’s Western, THE SQUAW MAN (1914), became Hollywood’s first full-length feature film, Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., starred in WILD AND WOOLLY (1917), a.k.a. A REGULAR GUY, a Western comedy by director John Emerson for whom Anita Loos wrote the script and Erich von Stroheim served as Art Director. The plot concerns an Eastern railroad scion sent west by his father in an attempt to cure him of his romantic notions of Western life. A fake train robbery and Indian raid are meant to give the kid a thrill, but a real villain gets into the act, inspiring our tenderfoot hero to perform acts of courage with live bullets, not the blanks dad’s men had provided for him. OUT WEST (1918), a silent short starring Fatty Arbuckle and Buster Keaton set in Mad Dog Gulch, “the toughest town in the movies,” kept the laughs coming.

The classic Western comedy from Hollywood’s golden age was DESTRY RIDES AGAIN (1937) starring Marlene Dietrich, in which James Stewart as a pacifist sheriff finally finds his gumption, straps on his guns, heads over to the Last Chance Saloon and restores order to the wild and woolly town of Bottleneck. According to the AFI Catalog of Feature Films, the Hays Office ordered Universal to delete the line of dialogue, "There's gold in them there hills," which Dietrich says as she stuffs a handful of gold coins into her bosom. Although Universal agreed to delete the offending line, a print shown in New York escaped the censors and caused a scandal. "See What the Boys in the Back Room Will Have" became Dietrich's signature song. She frequently performed the number in USO shows and nightclub acts, and it is still showcased in performances by Dietrich impersonators today. The number also inspired Madeline Kahn’s hilarious Dietrich send-up, “I’m Tired” in Mel Brooks’ BLAZING SADDLES (1974).

The classic Western comedy from Hollywood’s golden age was DESTRY RIDES AGAIN (1937) starring Marlene Dietrich, in which James Stewart as a pacifist sheriff finally finds his gumption, straps on his guns, heads over to the Last Chance Saloon and restores order to the wild and woolly town of Bottleneck. According to the AFI Catalog of Feature Films, the Hays Office ordered Universal to delete the line of dialogue, "There's gold in them there hills," which Dietrich says as she stuffs a handful of gold coins into her bosom. Although Universal agreed to delete the offending line, a print shown in New York escaped the censors and caused a scandal. "See What the Boys in the Back Room Will Have" became Dietrich's signature song. She frequently performed the number in USO shows and nightclub acts, and it is still showcased in performances by Dietrich impersonators today. The number also inspired Madeline Kahn’s hilarious Dietrich send-up, “I’m Tired” in Mel Brooks’ BLAZING SADDLES (1974).

The greatest comic personalities of the ‘30s and ‘40s applied their brand of humor to the comic Western genre. In WAY OUT WEST (1937), Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy deliver the deed to a goldmine to a dead prospector’s daughter. Oliver also delivers the immortal line, “This is another nice mess you’ve gotten me into!” Allan Dwan’s TRAIL OF THE VIGILANTES (1940) corralled Franchot Tone, Warren William and Broderick Crawford in the story of an undercover reporter sent to investigate a murder. Naturally, he falls for the local sweetheart and helps bring the bad guys to justice. Mischa Auer, the “mad Russian” specialist, is cast as a Cossack cowboy.

GO WEST (1940) features the Marx brothers in a frantic race to capture the deed to Dead Man’s Curve and sell it to the railroad before a team of swindlers beats them to it. Of course, they succeed, allowing true love to triumph, and proving Groucho’s dictum as S. Quentin Quale: “Time wounds all heels.” Mae West and W. C. Fields co-wrote and starred in MY LITTLE CHICKADEE (1940), a Western in which she tames rowdy schoolboys while he tends bar and becomes the unlikely sheriff of Greasewood City. The comedy team of Bud Abbott and Lou Costello also got in on the Western act with RIDE ‘EM COWBOY (1942), treading the well-worn path of the transplanted Eastern tenderfoot. The poster art for the film features Bud and Lou wearing cowboy chaps and Indian headdresses. In 1948, Bob Hope starred as “Painless” Peter Potter, a dentist, in the Christmas release of THE PALEFACE with Jane Russell as Calamity Jane. Even before the feature started, audiences could catch a comic Western short like BUGS BUNNY RIDES AGAIN (1948), in which Yosemite Sam is “a-lookin’ for any varmint that dares to tame him.”

The 1950s saw the rebirth of traditional Westerns and the rise of revisionist storytelling – both expressed in a grittier, more psychologically complex style. A more naturalistic approach to acting the hero – or anti-hero – reflected the influence of the Actors Studio and the emergence of new stars like Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift. Yet even in the decade that gave us HIGH NOON (1952) and SHANE (1953), there was room for musical comedy in ANNIE GET YOUR GUN (1950), A TICKET TO TOMAHAWK (1950) and RED GARTERS (1954) – as opposed to singing cowboy films, another genre altogether – and mainstream cornball laughs in CURTAIN CALL AT CACTUS CREEK (1950) with Donald O’Connor, FANCY PANTS (1950) with Bob Hope and Lucille Ball and THE FIRST TRAVELING SALESLADY (1956) with Ginger Rogers.

The 1950s saw the rebirth of traditional Westerns and the rise of revisionist storytelling – both expressed in a grittier, more psychologically complex style. A more naturalistic approach to acting the hero – or anti-hero – reflected the influence of the Actors Studio and the emergence of new stars like Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift. Yet even in the decade that gave us HIGH NOON (1952) and SHANE (1953), there was room for musical comedy in ANNIE GET YOUR GUN (1950), A TICKET TO TOMAHAWK (1950) and RED GARTERS (1954) – as opposed to singing cowboy films, another genre altogether – and mainstream cornball laughs in CURTAIN CALL AT CACTUS CREEK (1950) with Donald O’Connor, FANCY PANTS (1950) with Bob Hope and Lucille Ball and THE FIRST TRAVELING SALESLADY (1956) with Ginger Rogers.

The youth culture and anti-authoritarianism of the 1960s nearly stampeded the sacred cows of traditional Westerns right out of movie theaters. The “do your own thing” decade put a counter-culture spin on the lone gunman of Western legend in comedies like CAT BALLOU (1965), which at #10 is the only comedy on AFI’s Top 10 Western list and features a drunken gunfighter (Lee Marvin in his Oscar®-winning role as Kid Shelleen) who literally cannot hit the side of a barn; THE ROUNDERS (1965) with Henry Fonda and Glenn Ford as aging cowhands not quite ready to settle down; CARRY ON COWBOY (1966), in which plumber Jim Dale is mistaken for a lawman and flushes out the Rumpo Kid and his gang; THE SHAKIEST GUN IN THE WEST (1968) starring Don Knotts as a dentist who gains notoriety as a gunslinger; and SUPPORT YOUR LOCAL SHERIFF (1969) with James Garner as the man with the badge who’s more interested in a paycheck than any code of honor or sense of frontier justice. The Lerner and Loewe musical comedy PAINT YOUR WAGON (1969), with Lee Marvin and Clint Eastwood as singing prospectors, helped bring down the curtain on the decade.

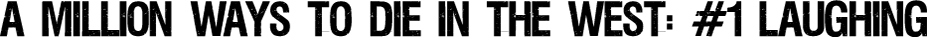

Ushering in the1970s, THE CHEYENNE SOCIAL CLUB (1970), directed by Gene Kelly, also cast traditional Western stars – AFI Life Achievement Award (LAA) recipients Henry Fonda and James Stewart – in a comic plot involving the inheritance of a thriving brothel. Two more AFI LAA recipients, Clint Eastwood and Shirley MacLaine, were paired in TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA (1970), a Western whose comedy was accentuated by Ennio Morricone’s “Braying Mule” score, which was recycled by Quentin Tarantino in DJANGO UNCHAINED (2012) – a comic musical motif dating back to Mendelssohn’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture” by way of Ferde Grofé’s “Grand Canyon Suite.”

Ushering in the1970s, THE CHEYENNE SOCIAL CLUB (1970), directed by Gene Kelly, also cast traditional Western stars – AFI Life Achievement Award (LAA) recipients Henry Fonda and James Stewart – in a comic plot involving the inheritance of a thriving brothel. Two more AFI LAA recipients, Clint Eastwood and Shirley MacLaine, were paired in TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA (1970), a Western whose comedy was accentuated by Ennio Morricone’s “Braying Mule” score, which was recycled by Quentin Tarantino in DJANGO UNCHAINED (2012) – a comic musical motif dating back to Mendelssohn’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture” by way of Ferde Grofé’s “Grand Canyon Suite.”

But the ‘70s film that forever changed the way we look at Westerns was made by AFI’s 41st LAA honoree, Mel Brooks. BLAZING SADDLES sprang from an Andrew Bergman screenplay entitled “Tex X,” which concerned a militant black sheriff in the Old West, whose moniker was a nod to Malcolm X. Brooks hired Bergman to join him and a team of writers, including Norman Steinberg, Alan Uger and Richard Pryor, in creating a go-for-broke send-up of racism, hypocrisy, greed and the cowboy genre. “We’re trying to use every Western cliché in the book – in the hope that we’ll kill them off in the process,” the director explained. Brooks cheerfully ignored those critics and others who described his work as vulgar, and liberated grateful audiences by acknowledging truths that had been missing from the screen. In the end, all mankind shared beans around his campfire, and another taboo was gone with the broken wind.

Gene Wilder, who co-starred as the Waco Kid in BLAZING SADDLES, made another comic Western five years later. In THE FRISCO KID (1979), he plays Avram, a Talmud-quoting Polish rabbi making his way across America to his new congregation in San Francisco, assisted by a bank robber played by AFI LAA recipient Harrison Ford. Not since the Tin Pan Alley piano tune, “I’m a Yiddish Cowboy,” gave Edward Meeker a hit as Tough Guy Levi in 1898, had Jewish culture and Western legend been so successfully combined.

Gene Wilder, who co-starred as the Waco Kid in BLAZING SADDLES, made another comic Western five years later. In THE FRISCO KID (1979), he plays Avram, a Talmud-quoting Polish rabbi making his way across America to his new congregation in San Francisco, assisted by a bank robber played by AFI LAA recipient Harrison Ford. Not since the Tin Pan Alley piano tune, “I’m a Yiddish Cowboy,” gave Edward Meeker a hit as Tough Guy Levi in 1898, had Jewish culture and Western legend been so successfully combined.

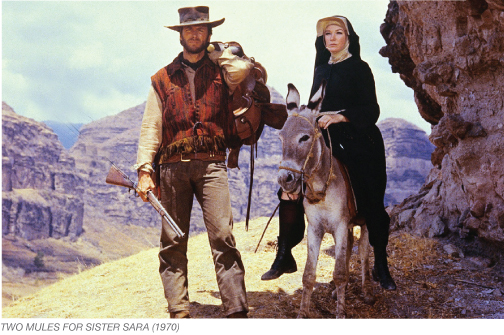

A campier campfire arose in the 1980s with LUST IN THE DUST (1985) starring Tab Hunter, Divine and Lainie Kazan. “He rode the West...the girls rode the rest” was its tagline. RUSTLER’S RHAPSODY (1985) spoofed spaghetti Westerns, and John Landis’ ¡THREE AMIGOS! (1986) boasted Steve Martin, Chevy Chase and Martin Short as three unemployed actors whose bandito act turns out to be the real thing.

In the past two decades plus, studios have unpacked a virtual wagon train of Western comedies: CITY SLICKERS (1991), a hit for Billy Crystal that was more of a contemporary story than an Old West comedy; LIGHTNING JACK (1994) with Paul Hogan as an Australian in the Wild West; MAVERICK (1994), an action comedy with Mel Gibson; WAGONS EAST! (1994), starring John Candy; ALMOST HEROES (1998) from director Christopher Guest; and SHANGHAI NOON (2000), a martial arts Western comedy starring Owen Wilson and Jackie Chan. As this last title suggests, the Western genre began to split into smaller subgenres during this period. In addition to traditional, revisionist and contemporary Westerns, there were now horror Westerns and sci-fi Westerns, fantasy Westerns and spaghetti Westerns, acid Westerns and Samurai Westerns – all riding into the sunrise of a new millennium.

In the past two decades plus, studios have unpacked a virtual wagon train of Western comedies: CITY SLICKERS (1991), a hit for Billy Crystal that was more of a contemporary story than an Old West comedy; LIGHTNING JACK (1994) with Paul Hogan as an Australian in the Wild West; MAVERICK (1994), an action comedy with Mel Gibson; WAGONS EAST! (1994), starring John Candy; ALMOST HEROES (1998) from director Christopher Guest; and SHANGHAI NOON (2000), a martial arts Western comedy starring Owen Wilson and Jackie Chan. As this last title suggests, the Western genre began to split into smaller subgenres during this period. In addition to traditional, revisionist and contemporary Westerns, there were now horror Westerns and sci-fi Westerns, fantasy Westerns and spaghetti Westerns, acid Westerns and Samurai Westerns – all riding into the sunrise of a new millennium.

Or was that a sunset? In the 2000s, Hollywood studios seemed to shy away from Western comedies like a horse near a rattlesnake. Small, independent films like PIZZA, PESOS AND PISTOLAS (2004) and SUMBITCH! (2009), the animated feature HOME ON THE RANGE (2004), and BANDIDAS (2006), an action film set in Mexico, came and went. Canada tried to take up the slack with GUNLESS (2010), a satirical look at violence in American culture. MAD MAD WAGON PARTY (2010), THE PLATINUM PEACEMAKER (2010) and SINGLE ACTION COLT (2010) all received scant attention. Otherwise, crickets. Tumbleweed. Where’d everybody go?

Enter Seth MacFarlane on horseback. Best known for TED (2012) and TV’s FAMILY GUY (1999-present), MacFarlane co-wrote, directed and stars in A MILLION WAYS TO DIE IN THE WEST as Albert, a cowardly Arizona farmer in 1882 who falls for Anna (Charlize Theron), leading to a showdown with her outlaw husband (Liam Neeson). A passel of talent, including Neil Patrick Harris, Amanda Seyfried and Sarah Silverman, rounds out the cast.

The trailer for A MILLION WAYS contains no fewer than seven ways – sudden deaths of the didn’t-see-that-coming variety except, that is, for the1.2 million moviegoers who did as of press time on Universal’s YouTube channel. These include being crushed under a huge block of ice, blasted by a drunk, dragged off by a pack of wild dogs, shot by an outlaw, maltreated by the local sawbones, set afire by an exploding camera and gored by a charging bull. “The American West is a terrible place in time,” says Albert at the local saloon. “Everything out here that’s not you, wants to kill you.”

The trailer for A MILLION WAYS contains no fewer than seven ways – sudden deaths of the didn’t-see-that-coming variety except, that is, for the1.2 million moviegoers who did as of press time on Universal’s YouTube channel. These include being crushed under a huge block of ice, blasted by a drunk, dragged off by a pack of wild dogs, shot by an outlaw, maltreated by the local sawbones, set afire by an exploding camera and gored by a charging bull. “The American West is a terrible place in time,” says Albert at the local saloon. “Everything out here that’s not you, wants to kill you.”

While a gang of film critics holes up in the mountains, trying out lines about a million ways to die at the box office, we see in MacFarlane a man who can bring back the laughter. And crouched behind our shutters, we wait for deliverance.

|

|

|

|

|