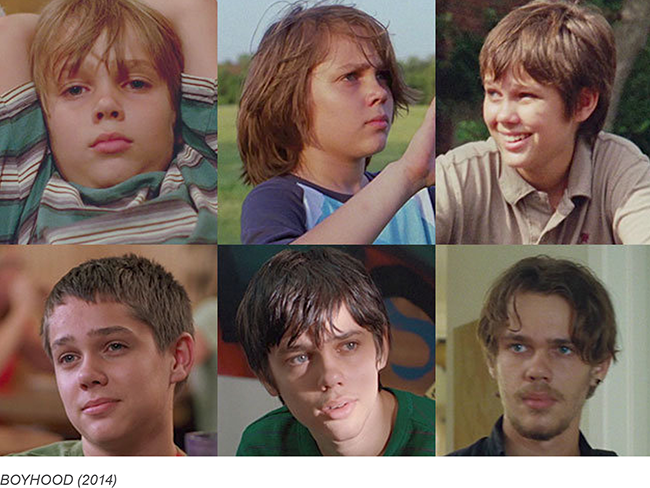

Seeing human beings age through time has always made compelling cinema. But BOYHOOD surpasses all that has gone before. The film was shot intermittently over a period of 12 years using the same cast. Without any special camera tricks or makeup, the actors age before our eyes in this epic and deeply moving film. The narrative scope accomplished in the film takes an art form existing for over 100 years down a pathway unmatched in the history of cinema.

Seeing human beings age through time has always made compelling cinema. But BOYHOOD surpasses all that has gone before. The film was shot intermittently over a period of 12 years using the same cast. Without any special camera tricks or makeup, the actors age before our eyes in this epic and deeply moving film. The narrative scope accomplished in the film takes an art form existing for over 100 years down a pathway unmatched in the history of cinema.

No surprise that Richard Linklater directs the film. Almost all of his films have an acknowledgement of time passing — most recently with the release of BEFORE MIDNIGHT (2013), the bookend to the BEFORE romance trilogy which spans 18 years of the main protagonists' lifetime. But there has never been a coming-of-age film shot like this before.

The fictional drama starring Ethan Hawke, Patricia Arquette, Ellar Coltrane and the director's daughter, Lorelei Linklater, traces a boy named Mason from first grade to college. On his journey, his divorced father re-enters his life; his mother moves their family and remarries; he experiences new schools and first love and discovers a talent for photography. And all the while, the actor's face, running parallel to his character's, changes from boy to man.

Linklater has given us slices of young lives before in DAZED AND CONFUSED (1993), SCHOOL OF ROCK (2003) and the remake of BAD NEWS BEARS (2005). Time has been significant in SLACKER (1991), DAZED AND CONFUSED and TAPE (2001), which all take place in one day; BEFORE SUNRISE (1995), BEFORE SUNSET (2004) and BEFORE MIDNIGHT (2013) follow a pair of lovers at nine-year intervals. But BOYHOOD takes these themes to the next level.

BOYHOOD, Richard Linklater's 18th feature since 1988, opens July 11, 2014, and has been the talk of the festival circuit, racking up several awards at Sundance, SXSW and the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year. Linklater modestly describes it as "some summer counter-programming." He spoke with us from his car while driving out of Austin, Texas, covering the miles with plain talk about what it took to make a film over a period of 12 years and his unabashed love for motion pictures.

Where do you begin with a film you know is going to take 12 years to make?

Where do you begin with a film you know is going to take 12 years to make?

This whole project was a huge leap of faith, obviously. You can't legally contract someone to be in it for the whole run. You just have to hope that it's worth it to them. I think artists have less trouble jumping into commitments because that's what they do all the time. For a businessperson, on the other hand, it is a bigger leap, thinking in a dollar sense.

And you had business folks who backed you?

We got lucky and someone gave us a little money every year to make the movie — or most of the movie. But, it's very different when you talk about kids, because a 6-year-old can't really make a life decision like that. Both of Ellar's parents are artists. I think they saw this as a potentially cool thing in his life — to be involved artistically in something like this.

How did you discover Ellar Coltrane?

He was a child actor with a headshot and résumé. I wanted to go that route — someone who had already, even as a kid, decided they wanted to act. But I hit the jackpot with him. There are a lot of kids who might have changed their minds, and decided they didn't want to act. But Ellar's an artist. Every year he brought more and more. He was always an interesting, fun kid to work with. He became an interesting teenager and, by the end, he's an interesting young man.

You have always been interested in the use of time in your films. Can you explain how its use affected the film?

Time was the wild card in all this. There was so much time involved that I wanted to use it for my ultimate advantage. I knew the plot would drift. It was part of the design. I didn't have to have it figured out in 2002, but I knew somewhere along the way it would work. It was a great luxury to have a year — every year — to think about it, to mold it, to have that gestation time, to watch last year's footage and to watch the whole film so far.

How did you re-orient the cast each year?

How did you re-orient the cast each year?

Usually, at the wrap of the previous year, I would talk a little bit about what I thought was coming next year, and then pretty soon there'd be a script or an outline. They got to work on it to varying degrees. I would occasionally show Patricia [Arquette] and Ethan [Hawke] footage. I wanted their meta thinking along with mine. I never showed the kids their stuff. I thought they might get self-conscious. With the adults, we had a chance to really think about what was coming up and start working on scenes. Sometimes we would be pulling it together at the last minute, too, so it ran the gamut of experience. But it was always gestating. It never just snuck up on me.

Were the actors ever concerned with aging in front of the camera?

I think Ethan and Patricia are so real and don't give a sh** about that. I never heard a word about aging. They were like: 'That's what I've done in my real life…' And they just kind of had fun with it. I remember when Ethan was looking at the movie early on and he was like, 'Oh wow, they grow up — we age." My daughter says it was hard for the young kids to watch themselves live through a very awkward age in front of the camera, even playing fictional characters.

You were thinking of a 120-minute film originally, and it grew to 164 minutes. How did it grow?

I've always done shorter movies that become epic in length. Every year, it just had its own life, you know? It wanted to be what it wanted to be. Some novels are 198 pages, some are 720, some are 1,500. The bottom line is we spent 12 years, and just about every film I go to is two hours and 40 minutes anyway.

'LIKE BEING COVERED IN JELLYFISH'

Unlike Mason, the character Ellar Coltrane plays in BOYHOOD, Coltrane has never sat in a real classroom. His parents homeschooled him, and saw in him a desire to act. Now 19 years old, and living in Austin, Coltrane talks about what it was like to spend 12 crucial years acting and growing up in front of the camera.

What was it like watching yourself as a child? It's incredibly bizarre. One of the strangest parts of watching the movie is watching the early years that I don't even remember and recognizing myself in that 6-year-old. You don't get that in a picture, you don't get that in a baby book. It's different.

What was your acting experience before BOYHOOD? I had done some commercials and a film called LONE STAR STATE OF MIND [2002], which was produced in and around Austin.

In the first scene of BOYOOD, Mason's mom remarks on his first grade teacher's comments about him. Were you an indifferent student like Mason? One of the biggest parts of Mason's life that is pretty different from my own is that I never really went to school as a child. I was homeschooled, and really unschooled in a lot of ways.

Who was your primary teacher, your mom or your dad? Both of them. I'm Iike Mason in that my parents are divorced, although they didn't get divorced until I was 10. My education was much more experiential than academic, which I think is good.

Did you take acting classes? I did a lot of theater stage acting when I was young, and I took a handful of classes at the Zachary Scott Theatre Center, here in Austin, and some private lessons with an acting coach. But I wouldn't say that acting was ever my primary focus growing up.

When did you see the finished film for the first time? Rick Linklater's advice was ‘Watch it alone, and watch it three times in a row, and then call me.' They brought me a Blu-ray, and I was able to watch it a few times alone at home before I went to any festivals. It was unimaginable. It's incredibly surreal, I suppose. It's a bit like being covered in jellyfish — incredible, emotionally very cathartic. I mean, now watching it, it doesn't have quite as strong of an emotional effect, but the first three or four times I watched the film, I was more or less catatonic for like an hour afterward.

For me, films are very much a part of my life. That's my GTO (automobile) in the movie. That's my pet pig on the iPhone while they're driving. My other daughters are in the movie briefly in the end, too. This movie's so personal that I think Lorelei picked up on that and just kind of had fun with it. She's a painter and she's been an artist her whole life, so I think this was just kind of an artistic undertaking she was involved in. When we started shooting this, she had already grown up on movie sets and been around my world, so it wasn't that odd for her to be on the other side of the camera.

Are there other coming-of-age movies that you admire?

It's a good genre — like all genres, when it's done well. For example, FANNY AND ALEXANDER. I don't know if that's coming-of-age. But the point of view is the kids' in that movie. They're sort of the victims, the heroes, so I'll be interested to see that again with this in mind. But like so often, Bergman got there first and did it better than anybody. I also like the way Truffaut had a real sensitivity toward kids, and I think that was probably the wounded kid in himself that would make films like SMALL CHANGE or THE WILD CHILD. He was very much in touch with that, which I find kind of wonderful.

It's a good genre — like all genres, when it's done well. For example, FANNY AND ALEXANDER. I don't know if that's coming-of-age. But the point of view is the kids' in that movie. They're sort of the victims, the heroes, so I'll be interested to see that again with this in mind. But like so often, Bergman got there first and did it better than anybody. I also like the way Truffaut had a real sensitivity toward kids, and I think that was probably the wounded kid in himself that would make films like SMALL CHANGE or THE WILD CHILD. He was very much in touch with that, which I find kind of wonderful.

Mason becomes a keen observer of life, and shows promise as a photographer. Do you see similarities between Mason and yourself?

Yeah, I'm sort of like that. I took pictures. I'm more of an observer. I'm more of an introvert than I am an active extrovert in the world — you know, a writer, a visual guy. So that's not far from home.

Your film has already garnered four awards on the festival circuit. Do you believe general audiences will turn out for a story about people, free of special effects?

Well, I've seen it with a lot of audiences now who all really enjoy it, particularly young people, people anywhere near the age of the characters. It's their lives. Essentially, we've got a film with a demographic that Hollywood would kill for — the under-25-year-old male. This is their movie and they love it. But that audience also doesn't rush out to see independent films. So it's a bit of a conundrum. But that's how every filmmaker feels. We've made a film that audiences will like, but how to get them to see it? That's not exactly my category. I'm not a marketing person.

A lot of moviegoers are going to feel invested in Mason's life. Are there any plans to revisit his family in the future?

Oh no. No current plans. I think that this was it. It was so much built on the grid of first through 12th grade — that whole thing about just getting out of school alive, getting to go off to college to be an adult at that point.

Oh no. No current plans. I think that this was it. It was so much built on the grid of first through 12th grade — that whole thing about just getting out of school alive, getting to go off to college to be an adult at that point.

Has your view of childhood changed at all in the making of this?

I think so. Having a kid, and making a film like this, was kind of an incredible life project. Every year was like: 'First grade, first grade — what was that like?' I've got a year to really think about one little incremental stage of development. Not like, 'Oh, childhood.' No, very specific. Then at the same time, really thinking about parenting, of course. It was a deep well of thought. You want to deal with subject matter that adds to your life in some way.

In the film, Ethan Hawke's character goes from being a singer-songwriter to an insurance salesman. What alternative path could you imagine for yourself?

I'm not sure. I wasn't quite a good enough student. I would be doing something in film. I'd be taking tickets at the theater, if nothing else. I'd be at AFI! I'd be in distribution, I'd be marketing and writing. You know, once I was into film — that was it. I was all in.

|

|

|

|

|