With a history that dates back to the early days of filmmaking, stop-motion animation has enhanced the art form since the late 1890s. This painstaking, frame-by-frame cinematic approach has been largely shelved in favor of its more technologically advanced cousin, CGI (computer-generated imagery); but there are torchbearers in the profession breathing new life into this timeless, meticulous technique. Enter the new magical film THE BOXTROLLS, coming to theaters this month.

With a history that dates back to the early days of filmmaking, stop-motion animation has enhanced the art form since the late 1890s. This painstaking, frame-by-frame cinematic approach has been largely shelved in favor of its more technologically advanced cousin, CGI (computer-generated imagery); but there are torchbearers in the profession breathing new life into this timeless, meticulous technique. Enter the new magical film THE BOXTROLLS, coming to theaters this month.

LAIKA Entertainment, from its studios located 950 miles away from Hollywood in Portland, Oregon, is leading the way to a new style of animation, gaining accolades and admirers from old and new audiences rediscovering the magic behind stop-motion animation. Less than a decade old and with two Academy Award®-nominated films (CORALINE and PARANORMAN) under its belt, LAIKA is quickly proving a force in the art form.

We sat down with Travis Knight, THE BOXTROLLS' lead animator and CEO/President of LAIKA, to discuss the studio's unique style of storytelling through the art of stop-motion. Throughout the conversation, it was evident that Knight's knowledge of the art form takes its cue from the masters who went before him, and is infused with a keen awareness of the technological aspects that will keep the traditionally mechanical process moving into the future of filmmaking.

THE BOXTROLLS is just the latest film to utilize the beguiling magic of stop-motion animation to its full, astonishing effect. Here are five memorable moments in motion picture history that gave life to images otherwise possible only in the imagination.

THE LOST WORLD (1925)

Before the release of THE LOST WORLD, author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle showed a clip of the film's dinosaurs to a group of magicians without any explanation about what they were watching — and those in attendance embraced the reality of the remarkably life-like images. Even The New York Times wrote, "If fakes, they were masterpieces." These images were, of course, both fakes and masterpieces. Thanks to special effects wizard Willis O'Brien, who helped pioneer stop-motion animation during the early years of cinema, these massive thunder lizards were able to interact with one another — and scenes such as the one in which an Allosaurus attacks an Agathaumas showed just how savage they could be. Frame by frame, O'Brien gave celluloid life to prehistoric creatures previously unseen by man.

KING KONG (1933)

At the start of the 1930s, O'Brien wasn't done using stop-motion to animate dinosaurs. His work on KING KONG featured a breathtaking battle between the monstrous ape and a fierce opponent — a Tyrannosaurus rex. But, unlike in THE LOST WORLD, this unruly beast doesn't engage exclusively with other large creatures. In this film, O'Brien's stop-motion took things further, bringing the titular beast into close contact with humans as well as monsters. O'Brien's masterful work made it possible for the 50-foot-tall Kong (really an 18-inch puppet) to wreak havoc on New York City and its rubber-necking denizens, convincingly crushing subway cars and destroying biplanes with his bare hands, while also evoking sympathy as the uniquely tragic figure at the center of the film's doomed romance.

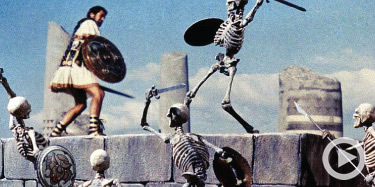

JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS (1963)

Having cut his teeth working under O'Brien on MIGHTY JOE YOUNG, animator Ray Harryhausen would go on to become the preeminent name among stop-motion artists — creating his own process along the way, which he called "Dynamation." His science-fiction work spanned the expanse from 20 MILLION MILES TO EARTH to THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS, but the great animator (who died in 2013) is perhaps best beloved for breathing life into legend and bringing creatures of myth to the silver screen. Amidst a career of creature achievements that include the Cyclops, the Kraken, the roc and beasties big and small, Harryhausen crafted the iconic climax for JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS — one of the artist's most memorable effects, featuring seven screaming skeletons risen from the earth to attack our band of heroes.

STAR WARS: EPISODE V — THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK (1980)

George Lucas' "galaxy far, far away" provided not only the far-flung backdrop for a new generation of artists to imagine the fantastic but also an opportunity for them to push effects technology in innovative directions. Phil Tippett and the Industrial Light & Magic animation team did just that in the STAR WARS saga's second installment — perfecting a process known as "go motion," which added blur between frames to create a more fluid motion effect. It is most notable in the film's iconic Battle of Hoth, during which the Rebels' remote ice base is laid waste by towering Imperial AT-ATs — massive, all-terrain, armored transports with deadly firepower and shields impervious to the heroes' blasters.

THE NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS (1993)

It had been nearly three-quarters of a century since THE LOST WORLD's debut when THE NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS was released in 1993. Tim Burton's ambitious musical ode to Christmas (or Halloween — or both) was done entirely in stop-motion — it took 13 animators three years to capture the film's endlessly expressive nuances. The impressive technical accomplishments are perhaps most visible in one of the movie's many musical highlights, "Jack's Lament," an elegantly intricate number that provides some of the film's most iconic visuals. Though THE NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS is bathed in Burton's signature style, it was heavily influenced by another holiday stop-motion animation classic: Rankin/Bass' RUDOLPH THE RED-NOSED REINDEER (1964), a beloved television special, which helped to spark a new era in stop-motion films and is still influential to this day.

How long have you been a stop-motion animator?

I've been doing this professionally for 16 years. It was a passion of mine when I was a kid, so I've been doing it most of my life in some form or other.

What drew you to this unique technique in filmmaking?

I've loved stop-motion since I was a kid. I loved animation of all forms. But, the Ray Harryhausen "creature features," like THE SEVENTH VOYAGE OF SINBAD and JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS, those things struck a chord with me. I think he's a touchstone for every stop-motion animator. One of the great regrets of my life is that I never got to meet him.

Do you have a favorite scene that resonates with you from those films?

The scene that I think most people would remark on is the one from JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS. The big battle with all the skeletons was so technically and artistically well done. As an animator, recognizing everything that he had to keep track of to make it feel fluid and alive, without having access to the modern technology that we have — you know, frame grabbers and that sort of thing — it's stunning.

Do you have an early memory of trying to experiment with the craft of stop-motion?

Yeah, I think that the things that I was doing early on are probably similar to the things a lot of people are doing early on at that age — just experimenting and trying to bring their stories somehow to life. I tried to do it in my parents' basement or garage, just experimenting. It was just figuring things out with trial and error. You know, your standard action-hero stuff and superhero stuff. It was just awful, garbage...It was more about learning the craft at that point.

How long did it take for the studio to create the world of THE BOXTROLLS?

THE BOXTROLLS has been slow-cooking in the studio since our inception. We started about 10 years ago. There were two projects that we took on just as we were getting going, and one of them was CORALINE (that was our first film) and the second project that we took on was "Here Be Monsters," written by Alan Snow, which is the book that inspired THE BOXTROLLS.

One of the things about animation that I love is that you can kind of distill the essence of an idea or personality or something into a visual design. Being able to echo and reinforce the main themes of the film in the design of the film was something that was exciting to our team of extraordinary artists. The actual production time is about a year and a half, about 18 months. All the stuff leading up to that, all the groundwork that we do to build up to the actual execution of the shooting of it, that took a good six, seven years.

Can you describe the essence or central message of THE BOXTROLLS?

For THE BOXTROLLS, our story was both personal and societal. We were exploring the meaning of family, an intimate connection between parents and their children, and we were juxtaposing that against this beautiful yet corrupted Victorian backdrop, stained by bigotry and corruption. We have a very personal emotion rooted in a lot of the filmmakers involved in making the film, which is that struggle that we all have as adults and parents who are trying to find a balance between meaningful work and family.

THE BOXTROLLS themselves are a metaphor for anyone who's been unfairly maligned or marginalized by the community, by their society. By layering all those things and folding those things on top of each other, we have a really rich personal experience, but also, you know, a fun movie experience for the family.

LAIKA Entertainment is revolutionary in the way it utilizes 3D printing in stop-motion animation. Can you describe that process?

We used 3D printing right from the start. One of the big technological breakthroughs that we had on CORALINE was using rapid prototyping to do the replacement faces. One of the biggest stumbling blocks with stop-motion animation is to make these characters feel alive. To make them seem like they have an inner life, and they're not some assemblage of steel and silicon; that they all are living, breathing, thinking and feeling creatures and not dolls.

Our hero, Eggs, he's only 9½ inches tall, and to make him feel like he's a living thing requires incredible subtlety and nuance. The old methods of getting that kind of facial performance, let alone the performance in the body, were insufficient to the task of making these things feel alive. That's when we started to explore how we could do this in a different way, and it came down to a unique approach in stop-motion, which is to embrace technology.

When you look back historically, technology was one of the things that undid stop-motion animation as a viable means of doing visual effects, because the computer usurped it. It was better at duplicating reality, and it had much more flexibility and all different kinds of wonderful qualities that stop-motion could not bring to the table. And so by embracing technology, and kind of fusing it with this old handcrafted methodology, we were able to find an incredible fusion of those things, which allowed us to do very expressive animation. [It was] the best of both worlds. We were able to hold onto the warmth of the handcrafted charm of stop-motion but give it some flexibility, some plasticity in the face, give it some nuance and subtlety that's often missing in stop-motion animation.

The villains in THE BOXTROLLS have an impressionist-painting look to them. Can you describe the design process behind this concept?

It's a further progression of the technology. On CORALINE, we integrated 3D printing rapid prototyping for the first time on a stop-motion film. It enabled us to give greater expressivity in the faces, but we had some costs with design, because you could only print in essentially black-and-white, you couldn't print in any color. On PARANORMAN, we pushed that forward, and we started integrating 3D printing where the color was infused into the print. So characters had more naturalistic skin tones and that sort of thing. The natural progression for that with THE BOXTROLLS was, now we know we can come up with very lifelike skin tones — let's apply a more artistic principle to that. And that's when we started to draw from impressionistic paintings and that sort of thing, to make the characters have that design sensibility. So you see these odd, opposing colors right next to each other in a way that you see the work of [Austrian painter] Egon Schiele, and that sort of thing. That's kind of reflected all throughout the set and production design, where you see it on the buildings and the clothing and the character designs and even in the skies. But you also see it in the skin, so you have these sort of weird, red and white lines kind of smashed up right next to each other. On a still, it looks strange, but when you see these things in motion, it just feels like this beautiful painting come to life.

What was the most difficult technical challenge working on THE BOXTROLLS?

THE BOXTROLLS was a very ambitious story for us; it required more and bigger environments, greater applications of technology, different processes, things that we started to figure out and learn on our previous two productions and then were able to apply to this. We created techniques and technologies along the way to realize the film. I think one of the things I'm proudest of with all our films, but I think it really comes to the surface on THE BOXTROLLS, is that fusion of production techniques. Our films are just a big gumbo of production techniques. We draw methods from things that predate cinema, from the stage, from early filmmaking techniques all the way up through current, cutting-edge CGI and technology.

I think with stop-motion generally, the most difficult things are on both sides of the spectrum. It's the big spectacle, the big action movement with the big kinetic camera moves, and it takes a lot to make it not feel like these are little dolls; to get that kind of organic feeling and personality in the animation and the camerawork and in the set design — that's very difficult on the one side of the spectrum. On the other side, [it's] the nuance, the subtlety, the refined sense that these characters are living, breathing creatures. So the way the character will shift its weight or take a step or breath or make slight adjustments in their face. That's also incredibly difficult to do when you're talking about an object that's only 9 or 10 inches tall. So I think on both sides of those things, we really struggled to make sure that this thing comes to life in the best way. It's a testament to the crew and how hard they worked and how much passion they had for the film that it comes together seamlessly. You don't feel the effort, even though it was an extraordinary effort.

What is the ratio of stop-motion to CG effects?

With all three of our films to date, they've all been hybrids of a sort. They all have elements of stop-motion, 2D hand-drawn animation and CG animation. Ideally, you can't tell what's what. Practically speaking, we try and capture as much stuff in camera as we can. I just think that helps. When you have real objects bathed in real light photographed by real cameras, things have a certain quality and a feeling that they don't otherwise. Whatever technique makes the most sense is what we'll do, but at its core, the lion's share of the film is something that was shot practically on stage.

Can you explain the importance of collaboration on your set?

Because we've now been doing this for three films, and each time we build on the processes and technologies from the previous film, we have this strange group of people, these Luddites and these futurists who work together, and each having a different approach to filmmaking that we can kind of figure out how each other works. It just makes the process that much more seamless. We don't have a post process in that sense. We have our post guys working with the practical guys right from the start, right from the inception of the project. So there's a constant back-and-forth through the entire production.

You have a great cast of acting talent in the film. Do you ever create a story with an actor in mind?

Well, I think that we don't typically think about casting early on in the process. The main energy is focused on getting a story that we believe in, that has a powerful core. When we start barreling toward production, that's when we really start thinking about casting in earnest. For our films, we want them to have a kind of a skewed naturalism — we don't want them to feel overly cartoony. So that means we want actors who can bring that kind of performance to the film, a very natural performance. You always want to feel that they are emotionally real, that there's authenticity there.

On this project, we wanted the antagonist to be one of the best animated villains ever. Right at the top of our wish list was Ben Kingsley. We thought that there's no way he would ever do it; he's a knighted actor, one of the finest actors who's ever walked the planet, and we went out to him and he was interested. When he said yes, we essentially celebrated throughout the studio — we couldn't believe it. The great thing there was, we had an idea in our heads of who Snatcher was as a character, and when we went to the first recording session, he came to the studio with a fully realized version of who he thought this guy was in his head. He sat down, and he did a performance in the vocal booth, and it was not at all what we expected. We were kind of shocked by what we were hearing, and yet as soon as we heard it, we knew it was perfect, that's who this guy is. So that's one of the great things that extraordinary actors can bring to it — they can give you the kind of perspective into the character you just didn't have before, and it was absolutely perfect. He did the whole thing essentially lying down because he felt like this guy, Snatcher, is a kind of guy ruled by gluttony. So he felt like he had to get the voice to come out of his gut, and in order to do that, he was lying down on the job to get the voice to come out of his body in the right way. It sounds nothing like Ben Kingsley, but it's an amazing performance.

LAIKA Entertainment has two Academy Award nominations under its belt. Is there a formula for the type of quality production your studio is producing?

LAIKA Entertainment has two Academy Award nominations under its belt. Is there a formula for the type of quality production your studio is producing?

I don't think it's a formula necessarily so much as it is an approach. The kinds of films that we aspire to make are films that are thought-provoking, emotionally resonant, progressive and just a wee bit subversive. We aspire to make films that are visually stunning, that have a patina of beauty, but more importantly have a reservoir of meaning. The combination of that approach, that philosophy and then the execution of that, how we make them, is also just kind of as unusual as that approach — that is, an employment of an age-old craft, coupled with science and technology and swirling in this kind of big gumbo of production techniques.

How does stop-motion animation contribute to the art of storytelling?

These are kind of our modern myths, films. There are few things that unite us more than a really beautiful film. I think that films in their best form speak to the shared humanity in all of us. I think that it's important for young filmmakers to recognize that these things don't happen on their own — only through extraordinarily hard work, thinking about these things and trying to take this medium that we all love, film or animation, and try and bring something new to it. Trying to bring a new voice, new ideas, kind of thinking about different ways to innovate within the space and converge technologies and artistry and just our personal experiences in some kind of fusion that gives us something unique to say. Animation typically tends to get thought of in simplistic terms as its genre, and I think that's [because] a lot of the films that have been made in the last 20-some-odd years tend to have a similar look and feel. But there's no reason you couldn't take this powerful, visual medium of animation and apply a different prism to it. Start to explore different kinds of stories and different ways. So that's the way we try to do it. I think if that were to happen more broadly across our industry — to take the prism of filmmaking and apply it to different kinds of stories and bring unique elements to it — I think that is what ultimately expands the palette of what you can do in this art. I think anyone working in film has an extraordinary opportunity to reach an audience in a unique way, and to not take advantage of that, I think we're doing the art and the audience a disservice. So I would hope more people take that kind of approach, where they think about how they can bring stories that are more personal and, because they're more personal, ultimately more universal and ultimately expand the horizons of the boundaries of what we can do in film.

|

Edit Here |

Edit Here |

|

|