What's your favorite film? Is there a movie that changed your life? Send us an essay of 500 words, give or take, about that film you can't forget — classic or contemporary — and we'll consider it for publication in these pages. In addition to your short essay, send your name, occupation, hometown, phone number, jpeg headshot and e-mail address to editor@AFI.com. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

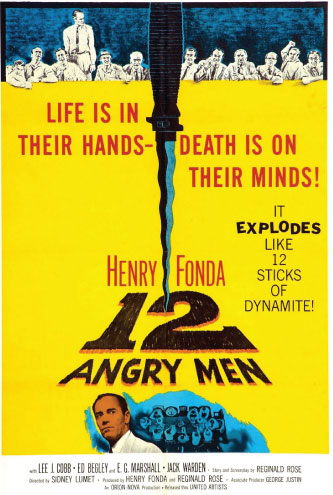

READER REVIEW: 12 ANGRY MEN

By M.E. Baz

M.E. Baz is a poet, cinephile and Web producer.

It has been my experience that we as people intuitively seek out reflection, in some form or another. One way we do this is through movies. We put ourselves in situations we've never experienced as a way to consider the choices we are capable of making.

It has been my experience that we as people intuitively seek out reflection, in some form or another. One way we do this is through movies. We put ourselves in situations we've never experienced as a way to consider the choices we are capable of making.

Sidney Lumet's 12 ANGRY MEN is one of the most powerful exercises in this form of reflection. The film is set on the hottest day of the year in New York City, and the action takes place almost entirely in a sweltering deliberation room, where 12 jurors must decide the fate of an alleged murderer. These men, brought together by fate or chance, must reflect upon not only the evidence at hand but also their preconceived notions, their choices and, ultimately, their lives.

So much of this film serves the purpose of putting the audience in the shoes of each juror. The anonymity of the men (we know them only by juror number) pushes us to consider that each of them could be any one of us — impatient, self-absorbed, defensive, uncertain, insecure, but also brave, thoughtful, responsible and urgently vested in the search for justice. We are all of these things. We carry our past and current experiences with us into every situation. The characters demonstrate as much as they reveal personal details. Juror 3's troubled relationship with his son, Juror 5's childhood living in slums, Juror 11's profession (watchmaker), and so on.

As the hours progress in the deliberation room, Lumet's camera positioning pulls us into not only the seemingly inescapable suffocation of the room, but also each juror's frame of mind. The camera begins above eye level, creating space between the subjects and turning the audience itself into a jury. Later, the camera moves to eye level: We have been unconsciously pulled into the room with them, making us equals. They are now a reflection of our own fallibility. In the last third of the film, the camera moves below eye level, increasing the tension in the room and the weight of the decision these men have been tasked to make.

Even the blocking of the actors plays with the idea of reflection. In the scene where Juror 10 reveals his racist reasoning for finding the defendant guilty, the other jurors turn away one by one, some turning their backs on him. This is not the first time one of the jurors has revealed his prejudice. Lumet's visionary filmmaking comes through in these choices, conveying to the viewer, "Not all things are reflected in one another, and you are not reflected in us." It is not a denial of the juror's bigotry, but a powerful statement on how as imperfect people we still are able to achieve the minimum self-awareness required to stand up to our lesser selves.

Even the blocking of the actors plays with the idea of reflection. In the scene where Juror 10 reveals his racist reasoning for finding the defendant guilty, the other jurors turn away one by one, some turning their backs on him. This is not the first time one of the jurors has revealed his prejudice. Lumet's visionary filmmaking comes through in these choices, conveying to the viewer, "Not all things are reflected in one another, and you are not reflected in us." It is not a denial of the juror's bigotry, but a powerful statement on how as imperfect people we still are able to achieve the minimum self-awareness required to stand up to our lesser selves.

Ultimately, in this murder mystery told in reverse, the defendant's guilt or innocence is not resolved. The audience, as an extension of the jury in the film, makes these reflections: We can rise above our imperfections. We can also decide on the kind of person we want to be, and on the type of relationship we want to have with the world around us.

Edit Here