BOURNE FOR ACTION

|

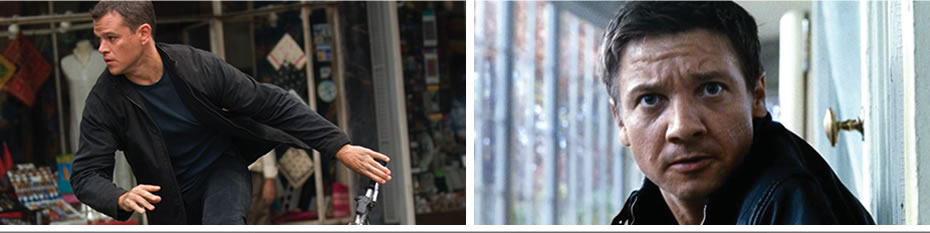

When THE BOURNE LEGACY opens on August 3, fans of the action series based on the 1980s spy novels of Robert Ludlum will recognize the throbbing, violent world of an experimental CIA program in which brainwashed operatives kill on cue with the precision of human drones. We can expect pitch perfect character work by the returning Joan Allen, Albert Finney, Scott Glenn and David Strathairn to lend a note of familiarity to Ludlum’s dark, clandestine landscape. But this time around, the sympathetic character of Jason Bourne, the amnesiac assassin played by Matt Damon who was the missing piece of his own puzzle in THE BOURNE IDENTITY (2002), THE BOURNE SUPREMACY (2004) and THE BOURNE ULTIMATUM (2008), will be gone, replaced by Aaron Cross, a new hero played by Jeremy Renner (THE HURT LOCKER, THE AVENGERS). According to Universal Pictures, Cross “experiences life-or-death stakes that have been triggered by previous events.”

Fortunately, those events were written by Tony Gilroy, who has not only scripted the latest Bourne installment but also directs it. Gilroy, son of Pulitzer Prize winning playwright Frank D. Gilroy (“The Subject Was Roses”), has previously written and directed MICHAEL CLAYTON (2007), which received seven Academy Award nominations, and DUPLICITY (2009). He is considered a master of the reversal – that sudden, surprising change of narrative direction found in the most sought-after Hollywood screenplays. Gilroy is also known for dialog that cuts to the quick of his beleaguered heroes. Here’s Jason Bourne sharing his sense of bewilderment with Marie, his imperiled companion in THE BOURNE IDENTITY: “I can tell you the license plate numbers of all six cars outside. I can tell you that our waitress is left-handed and the guy sitting up at the counter weighs two hundred fifteen pounds and knows how to handle himself. I know the best place to look for a gun is the cab or the gray truck outside and, at this altitude, I can run flat out for a half mile before my hands start shaking. Now why would I know that? How can I know that and not know who I am?” “Unlike the character they’re named for, the Bourne films with all their spectacular action possess a clear, direct birthright,” according to Dr. Steven Lipkin, Professor of Film, Video and Media Studies at Western Michigan University, author of “Real Emotional Logic” and a Bourne fan. “Hollywood has always manufactured spectacle, but the visual texture of global locations, chases, crashes, explosions, fights and myriad stunts only scratches the surface of what makes the three Bourne films to date distinct and identifiable.” “The Bourne films,” Lipkin explained, “are part of a long tradition that understands action films as melodrama." While in common usage the term “melodrama” implies the use of exaggerated emotions, which can make a film seem over-the-top and stereotypical, Lipkin is using the other, more academic meaning of the word, which relates to the dramas of the 18th and 19th centuries, where music or song accompanied the action. In fact, the word melodrama is derived from the Greek word melos, for music, and the French drame, for drama. “Scholarly and critical work on film melodrama since the 1970s has focused on the family melodrama and the ‘women’s film,’” said Lipkin, who has written about action films as male melodrama as part of a collection of articles entitled “Representing the War on Terror,” which will be published next year by University of Wales Press. “However, the film industry in Hollywood has throughout its history produced and publicized as melodramas westerns, war films, films noir, gangster films and docudramas.” As “prime examples” Lipkin mentions John Ford's IRON HORSE (1924), STAGE COACH (1939) and Gary Cooper writing out his will just before the climactic shootout in Fred Zinnemann's HIGH NOON (1952); among the war films, THE BIG PARADE (1925); WINGS (1927) and PLATOON (1986). “Think of Charlie Sheen watching Willem Dafoe not quite making it to the helicopter before the NVA finishes him off after Tom Berenger has tried fragging him,” advises Lipkin. Swashbucklers like CAPTAIN BLOOD (1935) and Hitchcock’s espionage/suspense films like NORTH BY NORTHWEST (1959) with “Cary Grant hanging onto Eva Marie Saint at the top of Mount Rushmore while Martin Landau is crushing his fingers with his heel” also prove his point. |

In what sounds to Lipkin like a concise description of the Bourne trilogy, film scholar Steve Neale, author of “Genre and Hollywood,” noted that these traditional melodramatic genres “meant crime, guns and violence; they meant heroines in peril; they meant action, tension and suspense; and they meant villains, villains who could masquerade as ‘apparently harmless’ fellows, thus thwarting the hero, evading justice and sustaining suspense until the last minute.” “Action in these films serves the basic melodramatic purpose of clarifying right and wrong," noted Lipkin. "But the action that has become the trademark of the Bourne films does so in ways that are also characteristic of melodrama – their action is rhythmic. It ebbs and flows musically, converting operatically the anguish of its characters into a visible choreography of movement.” Lipkin cites D.W. Griffith’s BIRTH OF A NATION (1915), BROKEN BLOSSOMS (1919) and WAY DOWN EAST (1920) as films that used accompanying music to comment on accelerated action and show the outcome of good triumphing over evil. Composer John Powell is credited with the distinctive original music of the original Bourne trilogy; for the new film, James Newton Howard, who has scored over 100 films, including THE FUGITIVE (1993), THE SIXTH SENSE (1999), THE DARK KNIGHT (2008) and, most recently, THE HUNGER GAMES (2012), supplies the score. “In the long-standing tradition of the action melodrama the Bourne films were born from, the energy of events alternates between constraint, containment and release in action,” said Lipkin. To illustrate his point, the professor cites each of the major action sequences in THE BOURNE ULTIMATUM, directed by Paul Greengrass. “They develop this dynamic interplay between action and restraint, expression and repression, and the open and the covert, as Jason Bourne’s search for the knowledge of his creation confronts the vast resources brought into play by the CIA forces that must stop him.” Early in the film Bourne arranges to meet a reporter whose stories suggest a source who can give Bourne the answers he needs. Bourne slips an untraceable cell phone into the reporter’s pocket and directs him through the crowded public space of London’s Waterloo Station. Ubiquitous video monitors mounted on buildings and streets and the numerous surveillance teams tracking their movements reveal to Bourne and us the encircling net the CIA has cast. “Bourne moves the reporter like a pawn, ordering him to stop, wait and then move again, each move quicker than the last,” Lipkin observes. “The scene cuts from Bourne watching the reporter and the surveillance, to the reporter, becoming increasingly afraid of the nearing danger, and the assistant director of the CIA calling the shots to his trackers. The net tightens, the reporter can’t get away and, without warning, Bourne knocks out the first mobile surveillance man. The pattern repeats. Finally the reporter, nearly hysterical, breaks from cover and is shot by a CIA sniper. Bourne snatches the papers in the man’s bag and gets away. Later, when another CIA assassin tries to kill Bourne in the streets of Tangier, the chase follows a similar progression of observation, fast movement, pause to reconnoiter, faster movement and then explosive violence.”

“When a bomb fails to kill him, Bourne pursues his would-be killer through streets, dodging gun shots, across roof tops, through apartments, finally catching him up in a fight to the death with knives and then bare hands in the confines of the smallest space the sequence can find: a bathroom. The ebb and flow of the action in these scenes as energy shifts from attempts to contain to evasion to the release of frustration in necessary action doesn’t simply reveal, but more importantly, makes a spectacle of the corruption and immorality of the power that created and now would constrain Jason Bourne.” And now that malignant power trains its sights on Aaron Cross. As a member of “the program” briefs us in THE BOURNE LEGACY trailer: “It’s Aaron Cross – we have never seen valuations like this. He’s Treadstone without the inconsistency.” With a trailer full of skidding motorcycles, snipers, stunts and explosions, it appears both the Bourne series’ legacy and Hollywood’s much longer legacy of music and melodrama, containment and release, will be honored in the new film. |

|

|

In 1988, ABC television aired a mini-series of THE BOURNE IDENTITY, starring Richard Chamberlain (DR. KILDARE, SHOGUN, THE THORN BIRDS) and Jaclyn Smith (CHARLIE’S ANGELS). It was directed by Roger Young (JESUS, JOSEPH) from a screenplay by Carol Sobieski (ANNIE, FRIED GREEN TOMATOES) and focused on the romance of Jason Bourne and Marie St. Jacques in a small French sea-side village. |