LEE DANIELS' THE BUTLER:

"IT WAS VERY, VERY, VERY EMOTIONAL"

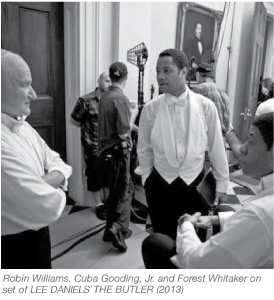

Director-screenwriter-producer Lee Daniels, whose 2009 film PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL PUSH BY SAPPHIRE premiered at AFI Fest and went on to win two Academy Awards®, spoke with us from New York recently. Daniels, whose work includes MONSTER'S BALL, THE WOODSMAN, SHADOWBOXER (his directorial debut) and THE PAPERBOY, discussed his most recent film, LEE DANIELS' THE BUTLER, starring Forest Whitaker, Oprah Winfrey, John Cusack, Liev Schreiber and Robin Williams. The civil rights drama set in the White House opens August 16.

Where did you grow up, and what were the movies that shaped your perceptions of the world?

Where did you grow up, and what were the movies that shaped your perceptions of the world?

I grew up in West Philadelphia, and the movies that really affected me? Several. A movie teleplay, CINDERELLA, with Lesley Ann Warren – child. WIZARD OF OZ – child. Older – GIANT. I went to the movies. PINK FLAMINGOS. Any of Bob Fosse's work – SWEET CHARITY, ALL THAT JAZZ. Fellini's work – 8 ½. There you go. And then later, LADY SINGS THE BLUES. All of which I felt were stories that really delved into truth or [had] acting moments that were interestingly told in a very truthful way.

Let's talk about your latest film. How did that project originate?

Right after PRECIOUS, my friend Laura Ziskin, who has now passed, asked me to read the script, and I thought that the story was interesting. The script needed work; it was a history lesson. I felt that the history lesson was interesting, but that we needed a heart – the family. We spent a little time on a rewrite and I submitted it to the studio. The studio wanted to do it, but just felt they needed to do it for a budget. The story spans 70 years, so it's sort of sweeping, it covers so much time, and time is money. It was too expensive. So we had to independently raise the money. During that time our producer, Laura Ziskin, passed, raising the money. Literally. I was writing. She was giving me notes on the script. She had cancer. You know, I had never intimately known anyone that was dying of cancer or that had cancer or was battling cancer, and I just thought she was going to live. She went in for some chemo and... [Pause.] I went to work on another film in the interim. It saddened me. And her. But it had been three years since PRECIOUS. And I needed to work. I went and developed another piece really quick and by that time, she passed – just as I was about to go into pre-production with THE PAPERBOY. Then, ironically, while we were shooting that film, this movie came together – THE BUTLER.

How does the film mirror the evolution of race relations in America?

That goes to story: A butler who lived through many presidents at the White House and how the civil rights movement affected his family directly. It's a father-son story. You know, that father-son story is universal. It speaks to no color in particular. The son is on a mission to fight for what he feels is right. African-Americans at the time...weren't allowed to vote.

Was any of that based on your own experience?

Based on my parent's experience. I vaguely remember the water fountains being different as a child, visiting my grandmother. And so yes, my experience, my parents' experience, my grandparents' experience. It's a very personal story to me because, though I can vaguely remember living it as a child, you know my mother and father certainly lived it and it hit directly home to them and my grandparents.

How do you think the butler would relate to Barack Obama?

I think he would relate to him. You know, it's interesting. I showed the film recently to my family on the Fourth of July in Philadelphia, and they were shattered. The older members of my family were shattered in a way that was incomprehensible to me. And I understand and I recollect. I think each generation of African-Americans are a generation away from what slavery and the post-slavery and the civil rights movement [meant]. There's a disconnect. I watched my 90-year-old cousin shattered at the memory. We go really from slavery to Obama's election. You really see it when you see it from beginning to end. It's sort of shocking, it's amazing – the journey that the country has been on. African-Americans have been on that journey and the whites that supported the civil rights movement, what they went through for black people to vote, [and to eat at the] same tables....The thing that my 90-year-old cousin sought, I saw it... At this point, I'm done with the movie. And so when I screen the film, I only watch the film through people's eyes. That's sort of how I judge the film. And it's like putting on a play, really, when you're in these intimate screenings for 40 or 50 people. People react differently. White people react differently than black people. Young people react differently than older people. So it was the first time I had shown it to an older group of African-Americans that were just... it was... oh God, it was very emotional – very, very, very emotional in a way that I hadn't experienced before because my children were moved by it, but they were disconnected from it. People that are my age understand it, and are touched by it. But people that have lived it, I mean, the older that you are, you live it!

For many years, the only roles available to black actors in Hollywood were maids, butlers, porters. What do you say to those who object to the portrayal of black characters as servants in a contemporary film?

I would say that for those who question the film, they should just see it. It's titled [LEE DANIELS'] THE BUTLER, and it's the story of the butler, but it's the butler's journey in the civil rights movement and how it affects his family. So we don't have a butler for the sake of being a butler and shining shoes. In the moment of the film, he happens to be a butler. To those who like to say, 'Shall I make a movie about a president?' I mean, 'How many presidents do we have? How many butlers do we have?' We tell those people to get real.

Do you believe black filmmakers have an extra responsibility, beyond telling true stories, to create a positive image of their people, given the relative scarcity of blacks on film?

Do you believe black filmmakers have an extra responsibility, beyond telling true stories, to create a positive image of their people, given the relative scarcity of blacks on film?

I mean... I'm the wrong person to ask that because I believe in telling the truth. On-screen, off-, my mama said, 'The truth will set me free.' And I get in trouble for that. I get in trouble for not editing myself in these interviews. I get in trouble on screen for telling my life, telling truths of people I know, stories I know, and I think that people are offended often by the truth. And so, for me, I have a responsibility to my children and to me.

Does your truth include encountering racism in Hollywood?

Mm-hm. For me to say that there isn't racism today, that would be untrue. But you can't use that as a calling card because the minute you embrace it, it becomes a reality, so I've never embraced it. I'm aware of it. It has happened to me, but I can't embrace it. Because then you live in that reality and then you're 'Woe is me. Oh, woe is me!' There is no 'Woe is me.' I care not to see it. And I've taught my kids as such.

Same issue with homophobia?

Same issue with homophobia?

Yes, I was about to say 'homophobia.' Exactly. I care not to see it. I have risen above it. Homophobia is rampant in the African-American community just as racism is rampant in America. We forget that. We live in New York, we live in Los Angeles – the metropolitan cities that interact with each other. That's not the heart of America. Far from. I'm reminded of that every time I go shoot a movie. It's in the heart of America where my A.D. or my location person who's white has to deal with people who won't let me in their homes.

Your first work in motion pictures was in casting. Is this one of your first considerations when choosing to develop a project?

Yes. Well, the story is first. It starts with the word. And, as you're writing, or when you're reading what someone's written for you, it becomes 'Who's right to speak these words?'

In LEE DANIELS' THE BUTLER, you have many major stars playing presidents and first ladies. How did you and casting directors Billy Hopkins and Leah Butler go about filling those roles?

The three of us. Billy works with me in New York. My sister Leah works with me in Los Angeles. Here's what happened with this case. First of all, I love and could not be happier with all the actors that we have in this movie playing the presidents and the presidents' wives. Sadly, though, there aren't any African-American names other than the Will Smith or Denzel [Washington] that would green-light the film. And if those two weren't in it, then the movie wasn't green-light-able. And then it's about: How will you get the money for the movie? Okay, you cast the movie with names. And it was those names that got the movie green-lit. That was the talent that I put together. So that's the reason we have the stars in the film – because without those white stars I wouldn't have gotten money. That's an indication of where we are right now.

Describe your working relationship with actors. Do you enjoy collaboration? Do you rehearse much?

I don't collaborate. I don't rehearse. I say, 'Say my lines.' There is no collaboration. [Pause.] I'm joking, oh God! [Laughs.] You have to know the actor, you have to trust the actor that you're working with because I don't have time for rehearsal. We don't have time for rehearsal because we don't have any money! And I've never had the luxury of having them. It's always been sort of 'in the moment' while we're there. But we've had tons of conversation about character, about where I'm going, about where the actor sees the character, so that when we're ready to shoot, we're on the same syllable, the actor and I, and we don't abrogate, we become one. It's a tango. It's like a dance. But if we're not on the same syllable, it's a catastrophe. And so far I've been very blessed. Magic. It's an interesting way of working.

So you stick to the script?

No, because often times the actor will have better lines than I have. And they've done a ton of research. And so I'll do it my way, and then we'll find the truth on the set. The actor will say, 'What about this?' 'Sure, let's give it a whirl.' And then maybe it's a hybrid of both that we end up with.

What was it like to work with Oprah?

We worked together on PRECIOUS. She was my executive producer and we had a relationship, but it wasn't on set. She was brought aboard post-PRECIOUS, and we became friends. And I told her we were going to find something to do together, and I was looking. The first thing I brought her was a serial killer and she looked at me like I was crazy. I thought it was a good script. I just thought it was a departure from the Oprah that we know. She said absolutely not. So I wrote this for her. The character was something else, and then I collected many women from the women that I knew in my life, and she said, 'I love the script.' 'Great, okay! Well, let me create something even better for you.' And we created a very complex woman, which you don't see very often in African-American women [on screen], who is supportive of her husband and her family and struggling with her own issues.

Was she apprehensive about returning to the big screen after 15 years?

Yes, I think a little. What I found marvelous about Oprah was her humility. I don't know what I expected of her on set, but it wasn't what I got. I got a very vulnerable, passionate actor. It took her a minute to render herself because she's very in control of everything. And so once we got over the hump of her rendering herself and losing herself, that's when the magic happened. Being in control doesn't mean that there was any arrogance. The control is done through humility and through many years of being Oprah. She didn't come on set with an entourage at all. She came on set with one person who drove her back and forth to set. And she stood in line like everybody else to eat the sloppy food that was served to us by catering. Prison food, we called it. So that, I guess, I was sort of surprised at – the normalcy in her wanting to be just one of the guys.

What was the greatest challenge in making LEE DANIELS' THE BUTLER?

It was really hard. There were several challenges. I think it was hard for me to direct some of the racial scenes that were there. It was very emotional. Many people were crying. White people were crying. Black people were crying. You know, the words that were used... some situations that had happened... re-enacting those moments were devastating to the human beings that were playing them. Shocking to those who didn't need a rehearsal or anything and knew exactly what to do and didn't have a problem saying pretty nasty things to people. Shocking to those of us who had problems saying those words or being subjected to it. It's hard, very hard. Raising the money was very hard. Pam Williams, who took the torch from Laura Ziskin to help, did a wonderful job – producer. It was really hard because, though everybody loved it, it's a very risky film. Film money is risk money and so it was risky to finance this film.

How does the new film compare with your other work?

How does the new film compare with your other work?

Well, it's PG-13, for starters. Other than that, the nuance of Lee Daniels is in everything that I do. The film is what it is. I am in all of my films. My life experience is on the screen always. And if I don't know the people that are portraying these characters then I won't put them on screen. I have to know these people. I have to have eaten with these people, I have to know everybody on screen. Now, I didn't know the presidents, but I did study...

Has it lived up to your expectations?

I'm biased, you know. I think so, yes. I'm very happy with it.

Is there an audience for serious drama?

I think we cannot underestimate the intelligence of the American public. I think that we continue to do that and, in doing so, we settle for mediocrity. And I think that good stories will always find a home in America.

What's next for Lee Daniels?

I'm developing a musical for film. Working on a play for Broadway. And there you go.

We'd love to hear from you. Please send your comments to Editor@AFI.com.

|

|

|

|

|