What's your favorite film? Is there a movie that changed your life? Send us an essay of 500 words or less about that film you can't forget – classic or contemporary – and we'll consider it for publication in these pages. In addition to your short essay, send your name, occupation, hometown, phone number, jpeg headshot and e-mail address to Editor@AFI.com. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

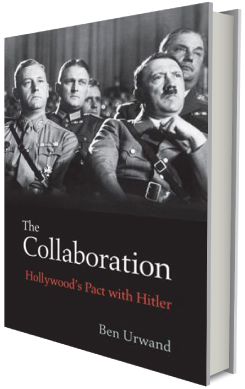

READER BOOK REVIEW: THE COLLABORATION

By Mike Greco

Mike Greco is a journalist and film historian whose articles have appeared in After Dark, American Film, Film Comment, People, Variety and the Los Angeles Times. A resident of Honolulu, Hawaii, his forthcoming books are "Reaching for the Stars: Paramount Pictures, 1912-1959" and "A Family Affair: The Warner Brothers Pursuit of the American Dream."

THE PRODUCERS, Mel Brooks' hilarious send up of unlikely bedfellows Nazis and show biz, would have benefitted greatly from a recently published "history" of Hollywood in the 1930s. The unintentionally funny "The Collaboration: Hollywood's Pact with Hitler" rivals Brooks' 1967 masterpiece for outrageous and bizarre characters, situations and plot twists. The big difference between the two is that THE PRODUCERS begs its audience to laugh whereas "The Collaboration" demands that its readers take its baseless assertions seriously.

Ben Urwand, author of "The Collaboration," argues that Hollywood's Jewish movie moguls kowtowed to Hitler's demands to censor all movies, themes, characters or scenes the Fuhrer or his representatives deemed offensive to the German people.

Urwand creates no loveable rogues like THE PRODUCERS' Max Bialystock, but instead creates a band of villainous latter day Shylocks – unscrupulous and cowardly – counting their shekels at the expense of the Jews being persecuted by the Nazis. "The studio heads," claims Urwand, "followed the instructions of the German Consul in Los Angeles, abandoning or changing a whole series of pictures that would have exposed the brutality of the Nazi regime."

The head Shylock and chief collaborator was allegedly MGM boss Louis B. Mayer. According to Urwand, "the most powerful man in Hollywood" took his marching orders from "the most important individual of the twentieth century [Hitler]." Mayer not only kept unflattering images of Hitler off the silver screen, he supposedly provided funds for German armaments. "It is time to remove the layers that have hidden the collaboration for so long," Urwand writes unaware or indifferent to the terrible libel he is committing, "and to reveal the historical connection between [Hitler] . . . and the movie capital of the world."

"The Collaboration" does not inform us if Mayer supplied the Fuhrer with popcorn when he screened MGM's sanitized movies.

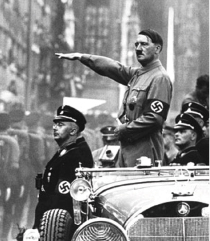

The young Hitler, Urwand claims, "turned his life into a film." Hitler's skewered historical reality was the product of countless hours watching images flicker across the silver screen. "He believed that they contained a mysterious, almost magical power that somehow resembled his own abilities as an orator."

"Hitler was obsessed with movies, and he understood their power to shape public opinion." "In Hitler's opinion," Urwand argues, "any struggle against an enemy had to be waged on two fronts. The first front was the physical battlefield, on which he believed that the German army had succeeded. The second front was the realm of propaganda, in which he insisted that the German government had failed." Hitler would not allow his soldiers to be "stabbed in the back" as he and his comrades had been. The Fuhrer would prevail on the propaganda front as well as on the battlefield.

Once he had become Chancellor, Hitler watched a movie every night before going to bed. The Fuhrer wished to be entertained above all else, and those films he deemed to be "gut" were usually guaranteed to play at Germany's best theaters.

According to Urwand, Hollywood's Jewish moguls were so eager to have their movies selected to play in Berlin they "collaborated" with the Nazis by cleansing American films of anything negative about Germany, its ruling party, its dictator, and especially its treatment of Jews. "The Hollywood studios put profit above principle in their decision to do business with the Nazis," Urwand charges. "Hitler was at the center of the collaboration."

One of the techniques Hitler used to gain and then hold power was to tell big lies that engaged his audience at the deepest, darkest emotional level. The Fuhrer defined the "big lie" as telling colossal untruths. Hitler wrote in "Mein Kampf" that "the masses would never believe that others could have the impudence to distort the truth so infamously."

Evidently, most reviewers of "The Collaboration: Hollywood's Pact with Hitler" cannot imagine that a Harvard University Junior Fellow "could have the impudence to distort the truth so infamously." These reviewers are very much mistaken.

Urwand claims Warner Bros. was the first Hollywood studio to try to appease the Nazis after Hitler came to power. He cites a pre-release screening of CAPTURED, a film set in a German prison camp during the World War, as evidence of Warner Bros.' "collaboration." Georg Gyssling, the newly arrived German Consul in Los Angeles, was invited to screen CAPTURED on June 15, 1933.

Gyssling vocally objected to almost every scene and demanded "a massive number of cuts." He described CAPTURED as "the most evil concoction to appear in the post-war period." Urwand suggests that screening CAPTURED for the German Consul and then making changes in the film was conclusive evidence of Warner Bros.' collaboration with the Nazis. But screening films for special interest groups was standard operating procedure in Hollywood during the 1930s.

"The picture industry is . . . hounded by foreign and domestic censorship of a type and a destructiveness which you are well familiar with," a Paramount executive wrote to chief censor Joseph Breen. "The ‘don'ts' which are handed to picture producers to observe are so numerous and of such a character that I wonder . . . how producers can continue to make pictures with any degree of entertainment in them." The executive continued, "after we have the don'ts laid down by Mr. Hitler, Mr. Mussolini, Great Britain, Continental Europe, Japan, China, Mexico and South America . . . the brewers appear." [A reference to a complaint from the National Association of Brewers about characters on screen becoming drunken clowns drinking beer.]

Jack Warner wrote his publicity chief: "It is true we have to fight the censor boards and long hairs and ‘never had done anythings' and ‘don't let anyone else do anything' and also ‘official organizations.' Thank heavens the public judges after all!"

Urwand argues that "Warner Brothers had a lot to lose" and protected its German interests by knuckling under to Gyssling's demands. However, the studio only made six cuts to CAPTURED, and these had been dictated by the Hays Office. Warner Bros. ignored "the massive cuts" Gyssling had demanded and released a version almost identical to what had been shown to Gyssling two months earlier.

The German Consul screened CAPTURED in a Los Angeles theater after its release, and, according to "The Collaboration," Gyssling was furious. He supposedly wrote to Warner Bros. warning the studio of "dire consequences" if they did not comply with his demands. Urwand admits that Gyssling's "letter has since been lost," but claims, "it is not difficult to guess what he would have written." "Guessing" about the content of a non-existent letter is one example of the author playing fast and loose with the evidence. The documents Urwand cites often do not say what the author claims or are not relevant to the text to which the note belongs. Many of the most sensational allegations in "The Collaboration" are not provided with any documentary citation.

CAPTURED was banned in Germany in January 1934 and labeled by the Propaganda Ministry as "the worst hate film made since the World War." "Collaboration" is a strange word to use for non-compliance.

Harvard University Junior Fellow Ben Urwand imagines another nefarious plot twist in his convoluted fairy tale about "Hollywood's pact with Hitler." According to Urwand, Warner Bros. realized they were in trouble with Germany about CAPTURED and attempted to assuage the Nazis with a film that condemned America for intolerance.

EVER IN MY HEART told the story of a German immigrant who experienced discrimination in America during the World War. Urwand argues that "just when the persecution of the Jews was beginning in Germany, Warner Brothers released a picture about persecution of the German minority in the United States."

Unfortunately for Urwand's thesis, EVER IN MY HEART was playing in theaters before "Warner Brothers knew they were in trouble."

Urwand incorrectly asserts that the Nazis "kicked Warner Brothers out of Germany for not making changes to CAPTURED!" But Warner Bros. made the decision to leave Germany and stop doing business with the Nazis.

Warner Bros.' Berlin representative, Phil Kaufman, was attacked by Nazi thugs on an anti-Semitic rampage in April 1933. They trashed his car, vandalized his home, and viciously beat him. The Nazis later apologized to him, explaining it was a case of mistaken identity. Kaufman died eight months later and Jack Warner believed the beating contributed to Kaufman's untimely death at age 49.

Another factor that prompted Warner Bros. to close its office in Berlin and leave Germany in July 1934 was the banning of its blockbuster hit, 42ND STREET, for being "too leggy." The most important reason for Warner Bros.' decision to leave the German market, however, was that their revenues from Germany were insignificant – certainly not sufficient to put up with Nazi nonsense much less to "collaborate" with Hitler and his minions.

"There's a whole myth that Warner Brothers were crusaders against fascism," the author of "The Collaboration" told the New York Times. "But they were the first to try to appease the Nazis in 1933." Incredibly, Urwand goes on to argue that Warner Bros. continued to "collaborate" with the Nazis even after they were "expelled" from the German market and no longer had business interests there to protect.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

During the 1930s, most Americans did not wish to become enmeshed in foreign disputes and embraced isolationism and non-interventionism. Several Neutrality Acts were passed by Congress designed to keep America out of foreign entanglements such as the Spanish Civil War. Hollywood was repeatedly warned not to take sides in foreign conflicts by various authorities from newspaper editors to members of the Congress.

Will Hays, President of the Motion Picture Producers & Distributors of America, wrote Jack Warner: "In my opinion, ‘hate' pictures have no place on America's amusement screen. Ministries of propaganda and public enlightenment may subject hapless populations abroad to such corrosive influences," but we must not.

Hays urged, "it is most earnestly hoped that the organized industry in the United States will continue to concentrate on entertainment." The man known as the "czar of the movies" concluded his epistle by praying that "no propaganda on screen shall be the contributing cause of making this industry assume the dreadful responsibility of sending the youth of America to war."

Defying public opinion, federal statutes, and the official position of their industry's trade organization, Warner Bros. made a series of anti-fascist feature films in 1937, culminating with CONFESSIONS OF A NAZI SPY in 1939.

BLACK LEGION, starring Humphrey Bogart and directed by Archie Mayo, was taken from 1936 headlines about a Nazi-like white supremacist group based in Detroit, Michigan that terrorized non-whites, immigrants, Catholics, and Jews in the name of "100 per cent Americanism."

Bogart portrays Frank Taylor, a typical American workman, hoping to be promoted to the foreman's job. The promotion is given to a "foreigner" instead and Frank becomes seduced by the hateful blatherings of co-workers who belong to the Black Legion. He joins the fascist brotherhood and ends up losing his family, friends, moral compass and his freedom.

Frank Nugent praised BLACK LEGION in his New York Times review as "editorial cinema at its best—ruthless, direct, uncompromising."

THEY WON'T FORGET, Warner Bros.' screen adaptation of Ward Greene's novel, "Death in the Deep South," "reopens the Leo M. Frank case, holds it up for review, and, with courage, objectivity, and simple eloquence, creates a brilliant sociological drama and a trenchant film editorial against intolerance and hatred." [Frank Nugent, New York Times]

Leo Frank, a Jewish-American manager of a pencil factory in Atlanta, Georgia, was railroaded for murdering 13-year-old Mary Phagan, one of his employees. Frank was convicted by flimsy circumstantial evidence and sentenced to die. The governor of Georgia commuted Frank's sentence and an outraged mob of leading citizens broke him out of prison and lynched him. The Frank case reveals the ugly truth about anti-Semitism in America as the Dreyfus case did in France. Redneck politician Tom Watson used the case to revive the Ku Klux Klan. Watson called Frank "a member of the Jewish aristocracy who had pursued ‘Our Little Girl' to a hideous death."

THEY WON'T FORGET is a powerful indictment against prejudice and intolerance, and reveals the plight of a hated "outsider," wrongfully accused of a crime, with the power of the state, the press and public opinion arrayed against him – a plight the Nazis were notorious for exploiting in 1937.

"In early February 1937," Urwand writes, "Gyssling called Warner Brothers, the studio that he had personally expelled from the German market several years earlier." Urwand continues: "He had heard that the studio was making a film about the French government's wrongful conviction of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer, for the transmission of military secrets to the German government in 1894. The film was obviously going to condemn one of the most notorious instances of anti-Semitism in the recent past, and Gyssling was determined to take action."

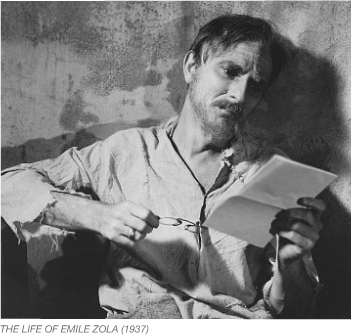

"The Collaboration" claims, "Just a few days after this phone call took place, Jack Warner dictated some important changes to the Dreyfus picture." "After all of Warner's changes had been implemented," Urwand gloats, "the word ‘Jew' was not spoken a single time in THE LIFE OF EMILE ZOLA."

"This unfortunate episode revealed what an aggressive figure Georg Gyssling had become." Almost admiringly, Urwand asserts that the German Consul "had dared to exert his influence over a studio that he had expelled from the German market."

Bowing to pressure from the Anti-Defamation League, Warner Bros. joined with the other major studios in 1937 and pledged to avoid using the words "Jew" or "Jews" in order to prevent a domestic anti-Semitic backlash to their films. It was obvious to everyone, including the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which awarded it an Oscar for best picture of 1937, that THE LIFE OF EMILE ZOLA was an indictment of anti-Semitism and fascist oppression.

Rather than hide from the anti-Semitic theme of their bio-pic, Warner Bros. aggressively marketed THE LIFE OF EMILE ZOLA in the Jewish community. Charles Einfeld, Warner Bros.' head of publicity, wrote Jack Warner: "In addition to complete coverage in the New York papers. . . [we] concentrated on publicity for the Jewish language papers. The returns from this source have already been very big…In this list were about 500 Who's-Who in New York Jewry. This latter list was entirely apart from a list of 150 of the foremost Jews in America, resident in New York, to whom Major Warner wrote a letter."

Warner Bros.' head of production, Hal Wallis, told the Los Angeles Times, "The screen world had discovered its editorial power. Like great newspapers, it can be influential for good." Wallis continued, "Biographical films such as . . . THE LIFE OF EMILE ZOLA are of great importance."

Jack Warner, quoted in the same article, cites THEY WON'T FORGET . . . and BLACK LEGION as "healthy influences upon our everyday life, which serve to open the eyes of the people to conditions far from ideal."

In May 1939, Warner Bros. released the first explicitly anti-Hitler, anti-Nazi movie by a major studio. CONFESSIONS OF A NAZI SPY was based on the personal experiences of retired FBI agent Leon G. Turrou (portrayed by Edward G. Robinson) who had busted a Nazi espionage ring operating in the United States in 1938.

Using newsreel footage including Hitler haranguing his brown shirt followers, CONFESSIONS has a quasi-documentary feel to it. New York Times reviewer Frank Nugent criticized Warner Bros. for making the Nazis "too villainous." Nugent, like most Americans, soon realized it was not possible to make Nazis "too villainous." Warner Bros. helped America come to that realization.

"The Collaboration: Hollywood's Pact with Hitler" claims that the Warner Bros.' reputation as anti-fascist crusaders was unearned and that the studio and its owners the brothers Warner were instead cowardly Nazi collaborators. This is a big lie similar to the ones Hitler told the German people.

Hollywood's Jewish moguls were mostly conservative Republicans during the 1920s. Harry and Jack Warner were the first to support Roosevelt in 1932. They used their influence with Roosevelt encouraging him to denounce Hitler, the Nazis and Germany as early as 1935 and continued to prod him until America declared war on Nazi Germany.

Harry Warner, one of the few devout Jews among the top movie executives, was an outspoken critic of the treatment of Jews in Germany. When MGM hosted Nazi newspaper editors visiting Los Angeles at the studio, an outraged Harry Warner wrote MGM executive Sam Katz: "I just can't bring myself to believe that your people would entertain those whom the world regards as the murderers of their own families."

Soon after Great Britain had declared war on Germany, Harry and Jack Warner purchased two Spitfire fighters for the Royal Air Force naming them the Franklin Roosevelt and the Cordell Hull. Perhaps the Warners' ultimate slap to Hitler's face was the stirring scene in CASABLANCA when Victor Laszlo drowns out Major Strasser by leading Rick's orchestra in a rousing rendition of La Marseillaise.

Harvard University Junior Fellow Ben Urwand has libeled Warner Bros. Don't believe him!

READER REVIEW: THE COWBOYS

By Michael Earle

Michael Earle works in private security and lives in Salem, Oregon.

Until recently, I was the insanely proud owner of an 800-title DVD and Blu-ray collection. My titles consisted of the works of my favorite directors: Ford, Hawks, Hitchcock, Stevens, Wilder and Wise and many others including Sam Wood and Edward Dmytryk. I owned premier classics from THE JAZZ SINGER to STAGECOACH to BEN-HUR to THE GODFATHER and beyond, with many guilty pleasures such as TEENAGERS FROM OUTER SPACE, HOT RODS TO HELL and THE ANGRY RED PLANET thrown in. I owned almost every Hitchcock title and everything that featured John Wayne from 1956 to 1976, with select titles from the years before.

Take THE COWBOYS (1972). First of all, it has an overture, intermission, entr'acte, and exit music – rare indeed for a picture released in the '70s, not to mention indicative of an epic (and, in this case, also intimate) tale. The basic story about a rancher resorting to driving his herd to market helped only by schoolboys is already a twist on familiar territory, but that's just the beginning. Bruce Dern gives a nuanced performance many years before other well-written villains such as DIE HARD's Alan Rickman. When Wayne's Wil Andersen and the cowboys watch a

fight between the old bull's "experience" vs. the younger one's "muscle," it serves as a metaphor for the entire picture (as well as John Wayne's place in pictures in 1972 among newish names like Hoffman, Voight – both of whom Wayne beat out at the Oscars® in 1969 – and De Niro). Then there's Robert Carradine's Slim serenading the cattle by playing Vivaldi on his guitar.

Director Mark Rydell set out to – and succeeded in – not making another "John Wayne picture." Nowhere do we see Harry Carey Jr. or Hank Worden, or Ben Johnson, or even Edward Faulkner. (How did that guy end up in so many of the Duke's pictures anyway?). In RED RIVER (1948), Wayne's Tom Dunson couldn't imagine being even just a little bit wrong. By the time of THE COWBOYS, Wayne had aged and seasoned like a fine old oak tree and could now play the subtle shades of a man who was at times deeply stubborn ("Well Mr. Nightlinger, In my regiment, I was known as...Old Iron pants...you might wanna keep that in mind.") but also haunted by self doubt regarding his two sons who had both died in their early 20s. ("They went bad on me...or I went bad on them.") It wasn't a cattle drive so much as it was a second chance for Andersen to be a father (as pointed out in one of many wonderful scenes between a rancher and his trail cook).

It's really quite amazing how different THE COWBOYS is from the Duke's previous westerns. From a director he had never worked with before – who created not quite a western revision, but with fresh, new ideas from screenwriters Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr. and respect for the star and his fans, more of an homage – to the graphic, bloody special effects make-up that Wayne was not too keen on, but endured anyway, to the rare fate that befell Wil Andersen, this is, I think, John Wayne's best picture of the '70s. THE COWBOYS is for anyone who thinks they don't like any John Wayne pictures. It may not change their minds, but it might open them.

My personal movie collection was not just a hobby to me. It was the one thing in my life that always had time for me and was never too busy for me. My collection was the closest thing I will ever have to children. Those titles...those pictures...those discs were my family. McQueen, Wayne, Holden, Eastwood, Mitchum, Heston, Douglas. Ingrid Bergman, Grace Kelly, Vivian Leigh. When it appeared I would never have a family of my own, they became my family – very much the way the cowboys came to replace the sons that John Wayne had lost giving him a second chance to be a father. Sometimes life has a way of fulfilling our needs in very unusual and unexpected ways.

When I was forced to sell my collection two years ago I felt as if my family had been taken from me, and a day doesn't go by when I don't think of my children – gone forever and in the hands of strangers.

Recently I purchased BEN-HUR on Blu-ray. I have hope that someday I'll be able to have a new collection.

We'd love to hear from you. Please send your comments to Editor@AFI.com.

Edit Here

|

Edit Here |